“Where’s the justice in that?” Loiza asked, his question interrupting the silence in Jake’s Cadillac sedan.

Jake wasn’t sure what his young assistant was talking about, but assumed it had to do with the man holding the cardboard sign on which uneven magic-marker lettering broadcast a plea to motorists stopped at the traffic light: Homeless. Lost Everything. Please Help.

Jake couldn’t help observing that the sign man had not lost his pants, but judging from the way they hung that could happen at any moment. So as not to seem insensitive, Jake did not point this out to Loiza, any more than how whenever he came upon one of the man’s destitute-like kind at intersections from city to county, he thought how his father used to refer to them as beggars or hobos, which Grace told him he wasn’t supposed to say any more.

Jake’s father had never used the terms in any derogatory sense. Those had merely been definitions used before people thought what you called someone could change the course of humanity instead of curing the ill that caused their situation. Jake’s father used to give money to the out-of-luck men—and it was always men back then, not women like Jake saw now, often with young children in tow. Although some of the cash Jake’s father handed out, he got back when the financial misfortunates came into his store to buy miniatures of rum.

When Loiza followed his initial question with another—“What do you think that cost?”—he was peering through the windshield up into the remarkably blue early-evening sky where a small jet slid sleek and fast toward the horizon.

Now Jake understood: Loiza was offended by the harsh visual juxtaposition of the man with nothing standing in tattered pants while a private jet (worth $5 million, Loiza had already checked on his phone) soared 15,000 feet over the man’s head of unkept hair.

Jake did not have an answer to Loiza’s not-entirely-rhetorical queries. Which Loiza was used to and would either let the subject go or keep talking. From the way Loiza plopped his phone on his lap and shook his head, Jake imagined it would be the latter.

The signal turned green. Traffic began to move. The man with the sign, having netted zero from the dozen cars Jake was stopped among, would soon have a chance to improve his luck with a fresh batch of homeward-bound commuters.

Loiza sighed, “The world is cruel far more than it is friendly.”

Jake wondered if Loiza read that somewhere. Or was it something that had come up in conversation with Grace, who shared Loiza’s sensitivities, which at times puzzled Jake considering his beloved Grace had killed her abusive husband and Loiza’s primary source of income was helping Jake murder people.

Jake once asked Grace how she felt about what he did for a living, and she said while she sometimes wished he was in a different line of work, if he hadn’t taken the career path he had, she would still be in jail, because Jake had been involved in something that allowed a deal to secure Grace’s early release on that manslaughter charge.

As to Loiza’s contributions to the hired demise of quite a few people now, Loiza said they were only the instruments of the deaths of the people they killed, like handguns with arms and legs. And as those NRA fellows could tell you, guns don’t kill people, people kill people. Or in their case, people hired Jake to kill other people. It wasn’t like they randomly went around murdering.

Jake imagined he was missing something in that logic puzzle, but whatever, Loiza slept well at night, unless his fortune teller mother with whom he lived was up to something, but that was another story.

Call it what you will, as for their evening’s agenda, Jake and Loiza were out in the county to remove someone from the roster of the living. Maybe.

First, Loiza needed to make a stop at a UPS Store.

Loiza’s mother, like many well-intended parents, had a habit of falling prey to advertisements for tech accessories hawked as being helpful to the “computer kid” in the family, when in fact the object was little more useful than a paperweight (and who used paper anymore?) But Loiza was a good son and pretended to be thrilled with his mother’s gifts, which he would promptly return and apply the proceeds toward something from a friend in China that was so technologically advanced newbie engineers at NSA would be baffled.

Directed by Loiza, Jake turned into a newer suburban shopping plaza, one of those many places where prosperous 30-year-olds who still cooked (and yes, microwaving was cooking) scrolled on their phones while clerks placed bagged groceries in the trunk of their SUVs, the size of which couldn’t fit within an elephant’s shadow.

For those yet to turn on the eight-burner stove that had been a $10,000 upgrade in their new home, a half dozen mediocre restaurants offered curb-side pick-up.

“Won’t be but a minute,” Loiza assured Jake, who waited in the car.

As Loiza headed for the UPS Store, the karate school next door let out and a dozen elementary-aged kids came bounding out in white gis, their faces flushed from exertion that involved more than their fingers and thumbs moving across a screen of some sort.

Loiza pretended to challenge the miniature martial artists, the tallest of whom barely came up to his belt. A bit of mock hand-to-hand combat ensued which quickly found Loiza down on the sidewalk, laughing and rolling around, his UPS package accidentally stomped on by his “assailants”.

One of the children’s fit yoga-garbed mothers came to Loiza’s rescue, picking up his trampled box and smiling as she handed it to him. Loiza smiled back. They chatted.

So much for this only taking a minute, Jake thought. But that was all right, they had plenty time.

When yoga mom gestured to the wine bar a few doors down—where a placard advertised liberal happy hours—Jake once again marveled at Loiza’s universal appeal. City, county. Old, young. Smart, dull. Women loved Loiza—even the women who didn’t usually go for tall, dark, and handsome.

Jake, on the other hand, appealed more to women attracted to bulldogs, and even then, he wouldn’t notice.

Jake’s view of Loiza was partially blocked when an imported after-market-modified Mercedes Panzer stopped in front of him. The Panzer sported a bumper sticker that read ENVY ME. Another announced: My Child Is an Uber Honor Roll Student at Valhalla Pre-K. Both stick-on proclamations were printed in UV-resistant ink, unlike the beggar’s cardboard sign a few miles back.

On the sidewalk meanwhile, Loiza exchanged phone numbers with the woman whose hair was styled in that shaggy multi-layered look that if Jake read Glamour he would know was called a “kitty cut”.

Jake’s further observation of Loiza became completely blocked when another glacier-sized SUV—a Range Rover something or other this time—stopped in front of him because it couldn’t get around the Mercedes Panzer.

When Range Rover tooted a move-along beep, Panzer woman furiously burst out of the Mercedes holding her phone, her enviable (according to her) diamond ring seizing the last of the setting sun’s reflective powers. “Do you mind!” she yelled. “I’m talking with my daughter!”

This was why Jake lived in the city, where this sort of bombastic carrying-on by entitled suburbanites tended to be discouraged by the ever-present threat of life-ending violence.

Out here in consumer Neverland, the high-income populous mistook their good fortune at having jobs for which society mistakenly believed they should be highly paid as a sign their lofty expectations were deserved and the rest of the world was their servants.

Jake, as he often did in situations like this, sat back and closed his eyes.

Nine minutes later, Loiza happily returned to the car, no longer in possession of his package but carrying a subtle scent that reminded Jake of an expensive hotel lobby. “Issey Miyake, I think,” Loiza said as Jake sniffed the air. “L’Eau d’Issey?” The woman’s scent lingered on Loiza’s forearm along with the memory of her touch.

“Your new friend?” Jake assumed.

“Yep.” Loiza placed the burner phone on which he’d entered the woman’s information in one pants pocket then retrieved his business phone from another.

“She married?” Jake asked.

“Divorced. Well, separated. Getting divorced. She seems nice.”

The Mercedes Panzer and Range Rover having trundled off without further altercation, Jake was clear to pull out of the parking space.

Loiza gestured across the plaza “We’re going to meet at that wine bar Friday night. Her son’s going to be with her ex—her almost ex. Soon to be ex. Unless you need me for something.”

“Knock yourself out,” Jake found himself saying, even though he hated that saying.

“Cool.” Loiza checked the map on his phone. “Right turn up here.”

“Got it.” Jake knew where they were going but didn’t mind confirmation. Not long ago, he would have bristled at that sort of instruction.

Ten minutes later, at a spot eleven miles across the city line, seven miles past the lost-everything man with the sign, three miles from the shopping center where Loiza and his new friend made a date for drinks, Jake took the turn toward Arbor Woods Country Club, a place its members would concede was just okay.

Arbor Woods had two passable 18-hole golf courses, a large swimming pool, a gym, pickleball and tennis courts, and a banquet room housed in an eye-catching mid-century modern building with a slanted flat roof and floor-to-ceiling windows that for a while had looked dated but was now back in style. Sometimes doing nothing was a plus in the world of design.

Arbor Woods’ most outstanding feature was that it was cheap, which well suited the county bar association. For a bunch who thought nothing of billing upwards of $350 an hour, lawyers were notoriously tight with a buck.

The upcoming evening’s festivities were to honor the Honorable Alexander Mint, who, having reached mandatory retirement age of 70, was stepping down from the bench after over two decades as a state district court judge.

Every lawyer in the county had been invited to bring a plus one.

While the gathering was ostensibly to celebrate Judge Mint’s judicial career, everyone planning to show—there had been a lot RSVP’d Regretfully Cannot Attends—anticipated doing so with great thanks to finally be rid of Alexander Mint. Except for one person.

If still alive, Norman Rockwell couldn’t have asked for a better model to paint the ideal farming wife than Dorothy Mint. Named after the Judy Garland character in the Wizard of Oz, Dorothy came from a family that had been dairy farmers since the county had two main roads and a horse was the main source of conveyance into Baltimore—which would be that bygone era when gunfire in the city was not unheard of, although generally had to do with whiskey and was not an hourly occurrence.

Dorothy was patient and pleasant, and a fantastic cook. Her sourdough bread was yeasty bliss, always kneaded by hand. The bread machine her daughter sent her for Mother’s Day a few years back had been donated in its unopened box to Dorothy’s church charity shop.

Dorothy Mint had no formal medical training but after a lifetime looking over the shoulder of veterinarians who tended the farm’s herd, if a neighbor’s cow had a breach birth and Dr. Tom or Al weren’t nearby, people called Dorothy. Of course, that was back when there were other farms.

There were still a few, but most had been sold off to developers who carved up rolling hillsides and squeezed in as many gigantic architecturally dull homes per acre as the easily duped bureaucrats at planning and zoning would fall for. Currently, those constructed monstrosities came in monochromatic shades of grey, white, and black, which was supposed to be trendy, and taste being what it was went for upwards of $1.5 million.

As other farms were sold off over the years, Dorothy’s late father hadn’t taken the monetary bait. Instead, he’d placed their 120 acres into a state-funded farm preserve, the personal benefits of which were practically zero other than some negligible tax savings and the state posting a sign on the front road informing anyone who drove by the idyllic setting that the land had been enrolled in a program that would prevent it from being turned into suburban blight regardless of greedy future generations who might wish otherwise. This was unnecessary as far as Dorothy was concerned, since she was an only child and loved the farm, but better safe than sorry.

In addition to her head of dairy cows, Dorothy adored crows and had since she was a child. Her collection of crow tchotchkes were prominently displayed in every room of the four-bedroom stone farmhouse where she’d lived her entire life.

Dorothy liked the birds’ brassy squawk and the way they strutted. She admired their wariness. She could throw out heels of bread every day and the same crows would approach her gifts with great suspicion, as if today was going to be the day she used bread to trap them. Only after convincing themselves of their safety would the crows beak-stab the bread, take a taste, then load it into their mouths and, with great effort, get airborne and carry it off.

The farm had always been hard work, but Dorothy enjoyed it. She couldn’t put in the hours like she used to and if it wasn’t for how her late cousin’s husband Milton modernized the operation and had them join a co-op 15 years ago, they would have probably gone over to all wheat, not just what they raised to feed the cows. And wheat wouldn’t have done well enough to keep the farm going. Of course, her husband’s salary—the judge—had been every bit as important to the farm’s survival as the cows.

Now that Alexander was retiring, they’d be okay with his pension, which wouldn’t be as much as his salary, but they’d still be okay. They’d be okay. Dorothy had been telling herself that for a couple years now, with her husband’s retirement looming on the calendar. And now here it was.

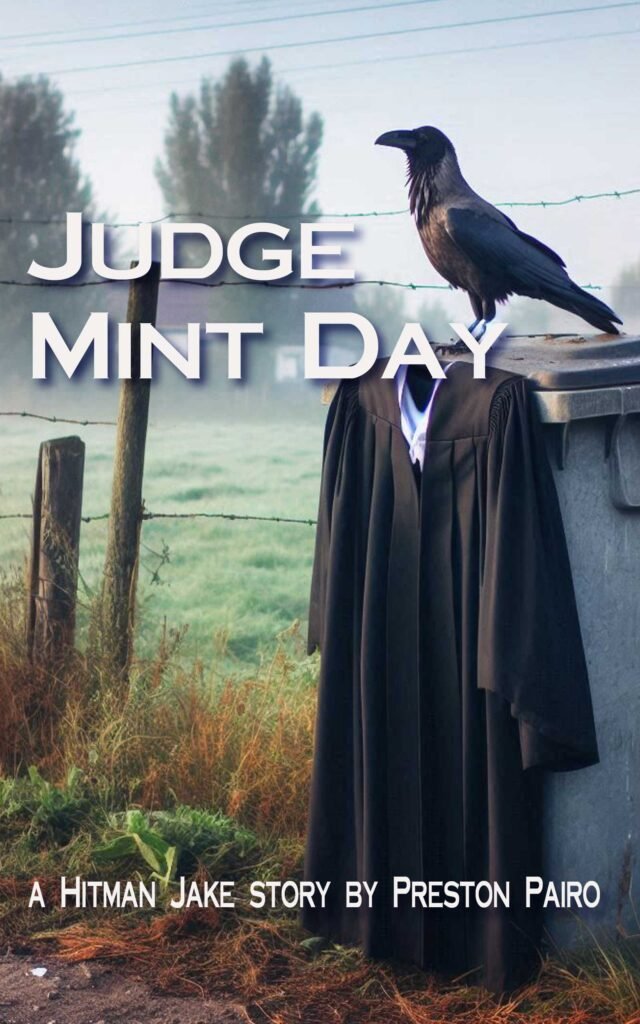

Dorothy Mint hoped tonight went well. She arrived at Arbor Woods early, just as the banner was hung over the banquet room entrance. Everyone in attendance would pass beneath the judge’s favorite saying, a phrase that if he’d been paid $1 every time he decreed it from the bench might have been a better retirement plan than that offered by the state: IT’S JUDGE MINT DAY.

Judge Mint always delivered that rather obvious pun with what he considered the aplomb of a religious zealot, his not-all-that-clever phraseology being how he referred to his impending determination of someone’s judicial fate. And while the line might have been novel to someone who’d never been in his courtroom before, lawyers stuck in front of him could be heard grinding their teeth as they suffered those ridiculous four syllables for the umpteenth time.

Once the sign was secured in place, Dorothy smiled and took a picture with her phone.

“What do you think?” That question came to Dorothy from Melissa Shore, the bar association’s events coordinator, who would have been a designer if her father had gone for it. Instead: law school—three years Melissa spent drawing what her interior decorating company’s logo would have looked like on pages of notes taken in classes she couldn’t have cared less about. But there she’d sat. And now she was a lawyer who did a little decorating on the side with two friends.

“It’s lovely,” Dorothy said of the Judge Mint Day banner. “Thank you so much.”

“Well, thank you, really, for understanding,” Melissa appreciated back. After all, it had been Dorothy Mint who’d paid for the banner, the treasurer of the bar association having said damned if he was going to have any part in memorializing a saying that every lawyer in the county—except one—despised hearing and couldn’t wait—couldn’t wait—not to have to suffer putting up with anymore once the old fart was finally—finally—off the bench. So Melissa had lied and told Dorothy there wasn’t money for the banner, and when Dorothy said how about if she paid for it herself, Melissa hadn’t been a quick enough liar to come up with a reason why not.

Of course Dorothy would never tell Alexander she’d paid for the sign, having used cash from the little farm stand she set up at the end of their lane, where she put produce from her vegetable garden and sometimes people would leave a few bucks, even though there was no sign asking for money. Dorothy just gave away what they wouldn’t be able to eat or can because even with all that the rabbits and deer devoured, crops tended to come in all at once.

So there the banner hung, big as day. Judge Mint Day. Yes, it was.

Dorothy smiled.

Melissa Shore hoped the sight of it didn’t give someone a stroke. She asked Dorothy if any of her children were coming tonight. When they’d spoken the other day, Dorothy said she wasn’t sure, because the Mints’ three children all lived far away and had family and job obligations—which was at least partially true. They all did live far away—and that was not accidental.

Starting with the child who would have had the longest plane flight to attend his father’s retirement dinner, there was Alexander Mint, Jr., who went to Japan on a hiking trip 25 years ago and hadn’t seen fit to recross the Pacific Ocean yet.

Years before Judge Mint first advised a defendant it was Judge Mint Day, Alexander Mint, Jr. suffered a different pun when middle school bullies, seizing the Jr. designation of his name, called him Junior Mint and proceeded to routinely pelt him with candies of that same name (although some used dollar-store knockoff Junior Minties candies, which was somehow even more insulting).

When Jr. sought Sr.’s paternal counsel how to handle the literally sticky situation, he’d hoped his father would consider letting him change his name. And not just the Junior part. He wasn’t that crazy about Alexander, either, which got shortened to Al, which the bullies who didn’t call him Junior Mint pronounced Al-lllllllllll, the way Peg Bundy addressed her dimwitted shoe-selling husband in Married with Children, which was nearing the end of its 11-year-run around that time.

Such wisdom, however, was not offered. Instead, Sr. confidently gave Jr. the old stand-up-for-yourself cliché, which foretold the lack of problem-solving skills Sr. would later bring to the district court bench. Because when Jr. stood up for himself, he found himself dragged into the school locker room where a jock strap smeared with melted Junior Minties was pulled over his head and he was made to turn circles until he fell over from dizziness and chipped a front tooth on a toilet bowl.

High school graduation hadn’t come soon enough for Alexander Jr., who that summer packed a duffel bag and bought a plane ticket with money saved from working in fast food, and was off to San Diego, where no one knew him. There, he learned how to surf and fell in love with a girl from Oregon who said she’d always dreamed of living in Japan so off they went and there they stayed.

Alice, the middle Mint child, lived outside Alberta, Canada, where she was married to a petrochemical engineer, had four children, and could be seen in the audience laughing at Jonny Harris’ kind-hearted comments about a resilient small town on a seven-year-old CBC broadcast of Still Standing.

At 18, when Alice, who had stellar SAT scores and was in the National Honor Society, told her parents she wanted to pursue a career in film, her father, without looking up from his newspaper, said, “No. End of discussion.”

Years before he was given constitutional authority to run a courtroom, Alexander Mint ruled his home like a dictator, and not the benevolent kind you sometimes hear people wistfully talk about.

Alice had replied, “Well if you think I’m going to study law … or farming, you’re out of your mind.” She’d looked straight at her mother when she said farming, and delivered the word with the intent to hurt that children can be so good at.

Dorothy had absorbed that pain by closing her eyes, and when she reopened them just seconds later, Alice was gone, and didn’t return home for a week, and then it was to start packing.

A month later, the oldest Mint girl took a train to New York City. She had an affair with a married man that (details remained sketchy) led to a semester at NYU. Which led to a brief acting career, including a role in King Lear at the Stratford Festival, where the director’s brother happened to be passing through long enough to fall in love with Alice and take her with him to Alberta, where she has lived ever since, remaining unapologetically distant with her mother and completely incommunicado with her father.

“I hope it wasn’t my fault,” Dorothy often ruminated about Alexander Jr. and Alice, including during a Zoom call two years ago with her youngest, Penelope.

Penny lived in Seattle, where she was twice divorced, childless, currently single and planning to keep it that way, and stayed in semi-regular contact with her mother, including Mother’s Day presents like the bread machine.

“But you all three were so headstrong,” Dorothy said during that call.

“And you wonder where we got that from?” Penny inquired, unable to conceal her incredulity.

“Well … Uncle George could be—”

“Mom. Mom,” Penny couldn’t help interrupting. “It was Dad. We got that from Dad.”

“Oh, he’s not headstrong. He’s wrong all the time and he must know that. You should hear some of the things he says. And it’s getting worse by the way, I can tell you.”

Penny could hardly manage a response, finally blurting, “You always stood up for him.”

“I wasn’t standing up for him. I was ignoring him when he got that way. I assumed you all were doing the same.”

“No, Mom, we were too busy having him ruin our lives. If he’s even worse now I can only imagine what he’s like as a judge. If it’s anything like he was as a father, I can’t believe no one’s shot him yet.”

“Oh, Penny, don’t say that!”

“I’m sorry, Mom, but it’s true. We never—none of us could believe how you put up with him. You know he hates the farm.”

“He doesn’t hate the farm.”

“Oh, come on, Mom. He hates it. Hates it, hates it, hates it. He was always muttering under his breath, saying, this goddamned place something or other. You had to have heard him.”

“I’ve said that. Farming can do that to you. Life can do that to you.”

Penny sighed, “Okay, Mom, whatever. I don’t know what to say. Let’s talk about something else. I didn’t mean to upset you.”

“I’m not upset.”

Which had made Penny smile, “No. You’re not. That’s what I love about you most. You don’t get upset. No matter what we did. You never got mad at us.”

“You were children. You’re still children. You’re my children. And I miss you.”

“We miss you, too.”

And then they talked about the cows. And everything was fine.

Besides, Alexander didn’t hate the farm, a fact proven when Dorothy met him in the driveway that very evening two years ago when he arrived home from court. Standing at the high point of the property where her ancestors located the original stone house, on the foundation of which Dorothy’s grandfather constructed their current home, they faced west admiring how the rolling fields soaked up the amber sunset and the old red barn glowed like a ruby.

Alexander said, “A multi-million-dollar view if ever there was one. City people don’t know what they’re missing.”

Down in the fields, the cows had mooed as if in agreement while the crows, because they were always wary of a trap, squawked.

But all of this information was the long answer to Melissa Shore’s question whether the Mints’ children would attend the judge’s farewell tonight, and the short answer, which was what Dorothy replied, was, “No.” A single syllable offered with a pleasant smile and no further explanation.

Tonight, the Mint family would consist of Alexander and Dorothy, as it had been before their three children were born and again since they all moved away.

Loiza showed Jake the aerial live-feed of the Mint farm on his phone, an image transmitted from a military-grade drone Loiza had picked up through a Chinese contact, an acquisition funded in part from returning useless tech-y gifts his mother had given him.

Loiza confirmed the ways in and out of the property they’d determined from an earlier surveillance. The only difference this evening was that a combine was moving across one of the fields, harvesting the season’s first wheat crop, which was always the thickest. But that shouldn’t cause any problems.

Jake nodded and sat back.

Across the street from the rural commuter lot where they were parked, a large man in overalls exited a Dunkin’ Donuts shop with an enormous colorful box that Jake suspected might be the man’s glazed dinner—but Jake kept that thought to himself.

Loiza, watching video of the combine as it created beautiful rows of mowed hay, asked Jake if he’d ever shot a deer.

Jake often wished Loiza kept his questions to himself but didn’t say that. Instead, he replied: “No.”

“Did you ever hunt?”

Jake looked at him.

“Animals?” Loiza specified.

Jake squinted.

“The four-legged kind?”

Jake shook his head.

Loiza said, “We used to shoot rats sometimes. When we were kids—my cousins and I. They’d get in the trailer where we used to live. And once I shot a squirrel. But I don’t know if I could do it now. They seem kind of defenseless. They don’t see it coming.” Loiza, picking up on the way Jake was looking at him, realized, “Oh, yeah…”

“All rise,” Frank the bailiff said, even though three of the four people still in the courtroom at that late hour were already standing, and the one who wasn’t was Betsy the court reporter, who needed a wheelchair and had been unsuccessfully trying to get that All rise practice removed from court proceedings for years.

As Judge Alexander Mint pushed up from his chair and adjusted his black robes, he thought, So this was it: the last time he would leave this courtroom. This was it. After 23 years.

Judge Mint remained stoic. His eyes were dry.

Judges’ benches in district court were not as high or ornate as those provided to circuit or appellate court judges, and required only two steps to descend, which Alexander Mint always considered as an affront.

“We’ll miss you, Judge,” Frank said quietly, offering his hand.

Judge Mint briefly shook Frank’s hand and nodded, then wordlessly passed through the door the retired state trooper held open for him.

Important to note is that when Frank said, “We’ll miss you,” he would have been hard pressed to find others willing to share that affection.

What Frank liked about Judge Mint was how he’d drag out court proceedings by reading applicable (according to the judge) sections of the Maryland Rules from that annually updated softbound tome, a hefty, dull (albeit mostly necessary) publication that would become so curled and worn from the judge’s constant use it barely survived until the issuance of the next year’s edition.

Judge Mint’s rule-reciting (which included a droning delivery and stern raised finger should anyone seek to interrupt him) infuriated most, but not Frank, because anything that caused a court session to run long was fine with him. Since Frank’s wife died a few years ago, Frank couldn’t stand the idea of being home by himself, and everyone was wrong about time making grief better.

Hopefully, the judge’s replacement would also keep court in session well beyond sunset on those dreary winter days Frank dreaded most. At the moment, however, it was just 5:15 as Judge Mint (or was he retired Judge Mint already? he wondered) made his way toward chambers along the windowless hall, where pale-grey walls matched his complexion.

His final day did not cause him to reminisce. He did not concern himself with how he would be remembered when people looked at his portrait in a plain wooden frame in the clerk’s office, the latest in a string of judges to have presided over this prosperous county.

Judge Mint would stand on his record. Which was a rather generous opinion for the judge to have of himself, for not only had a substantial number of his decisions been decided far differently on appeal, but failed to account for the many, many, many cases lawyers had finagled out of his courtroom in the first place by a variety of measures, some testing the boundaries of ethics by which attorneys were (add laugh track here) bound.

The prosecutors in circuit court even had what they called a Mint Docket, which every other week consisted of a few dozen cases removed from the district court by defendants requesting to have their case heard by a jury. Most of those defendants didn’t really want a jury trial at all, but saying those words got them out of having to appear before Judge Mint, since district court judges lacked constitutional authority to preside over jury cases.

Which was not to suggest being a district court judge lacked weighty responsibility. Judges in the state’s lowest rung of the judicial ladder touched the lives of more citizens than any others. Traffic court alone could bring a hundred or more ticketed drivers before one judge on a single day. Rent court was likewise log jammed. The DWI docket (always a good opportunity for proselytizing from the bench) remained busy no manner how many don’t-drink-and-drive advertisements were run, plus now there were all the stoned legal-marijuana tokers.

The sheer volume of cases often made the job tedious and mind-numbing. Most court sessions subjected a district court judge to a sanity testing bevy of kindergarten-level excuses and obvious lies. The intellectual experience could feel as far removed from the deep-thought academia of law school as a lawyer could ever land, save employment as a lobbyist. If compared to the staff in a four-star restaurant, a district court judge fell closer to dishwasher than chef.

But still, the salary was pretty damned good and included a long list of benefits, and removed the worry of having to chase after clients who didn’t pay their bill. Which was why lawyers sat outside the Governor’s door like eager fans waiting to buy concert tickets when a position opened.

Lots of judges handled the responsibility very well. A solid grasp of the law was important, but a sense of humor really helped. If that humor was self-deprecating, even better. A judge in a neighboring county often said that a donkey could do his job. (He used to say monkey, but people started taking offense to that, so he adeptly made the switch.)

Another of Judge Mint’s brethren routinely commented that this was the express lane of justice, and while she promised to do her best (and in fact always did) if someone believed she’d made a mistake please file an appeal so the matter could be heard in a higher court, where the dockets were shorter and the judges each had their own clerk instead of sharing one overworked law student.

Alexander Mint possessed none of those helpful qualities. In fairness, he wasn’t born that way, and nothing in his upbringing, legal education, or marriage had stood much of a chance of making any improvements. His personality was not, as lawyers often remarked with sarcasm when Judge Mint strode sour-faced onto the bench, “Minty fresh as always.”

All of which frequently begged the question: how did Alexander Mint get that judgeship in the first place? For that, back-peddle 25 years to what was then an even far different world than quick comparison would suggest.

Judge Mint’s father had been a successful businessman, and though he would eventually die bankrupt in Florida (nothing new about that), in his prime his fingers had dipped into a series of very profitable pies. Alexander Mint’s mother, meanwhile, was descended from an impressive line of state founding fathers.

With their combined connections, young Alexander Mint’s parents helped channel millions of dollars into the election coffers of numerous political candidates, including the governor who appointed Alexander to the bench.

Turn the calendar back further and discover that the day Alexander Mint was old enough to develop thought, he mistook the dumb luck of being born to parents of influence as indicating he somehow merited respect if not outright adulation, and his formative years of unimpressive education and failed athletic endeavors did nothing to dissuade him of this opinion.

His graduation from a mediocre law school only served to inflate his already puffy self-aggrandizement, conveniently overlooking his diploma was acquired with an embarrassing GPA that was best forgotten. Passing the bar exam was hardly support for his serendipitous ego, as witness scores of others who had survived the same multi-day test in the decades since, as that examination remained no more predicative of an individual’s ability or likelihood to properly represent clients in legal matters than throwing a dart at a distant board in a hailstorm.

The same state that required driving instructors to serve six-month apprenticeships willfully released lawyers onto the unsuspecting public without a modicum of hands-on supervision.

These realities were lost on Alexander Mint, excluded from his thoughts as though the black robes he wore were a barricade against logic. For 23 years, Alexander Mint went about every minute of every case he ever decided as though he was not only well-educated but innately wise.

He had treated his children much the same way, even how he held up his finger to silence questions or rebuttal, although at home he would sometimes say, “End of discussion.” Never, ever however, did he speak that way to Dorothy. Because only Dorothy’s name was on the deed to the farm. Her father had seen to that.

Live there as long as he had, make substantial financial contribution toward the upkeep until the cows literally came home, there was only one way Alexander Mint would ever own that farm—those glorious 120 acres that were worth millions if they could wrangle the property out of that state farm preserve program. Which Alexander Mint had been researching. Alexander Mint had a plan. And tomorrow, he was going to get started on that plan, in earnest. But first, there was his retirement dinner.

Judge Mint had two speeches prepared for tonight, each very different from the other. He still wasn’t sure which one to deliver. The one he wanted to use, or the one he was expected to use.

At Arbor Woods, the grumbling became louder as the time closed in on 6:15. The invitations had been clear, printed in a bold font: Drinks and appetizers at 6:30. Dinner at 7:00. Because it would be like old fart Mint to let his last docket drag on halfway into the night, keep everyone waiting for him to arrive at this banquet.

The Vice-President of the Bar Association, Tom McMillan (no relation to the former University of Maryland basketball star and not nearly as tall), had already ordered the hors d’oeuvres (such as they were) to be brought out and said Mint or no Mint, dinner was starting at seven and not a second later.

Unawares of this growing discontent, Dorothy Mint stood near the banquet room door, sipping a plastic cup of cheap white wine as she kept an eye on the lobby. She was eager to see Alexander’s expression when he spotted the banner.

When a uniformed waiter offered a tray of pigs in the blanket, Dorothy thanked him, took one, and proceeded to eat it without giving a second’s thought to what part(s) of the pig had been ground into that tiny sausage (because farmers have known where their food comes from long before current generations thought they invented the idea).

Five minutes later, Dorothy accepted a different waiter’s offering of a cheese triangle, which sat atop a dry store-brand cracker. That someone had taken the time to carve such precise geometric shapes from a car-battery-sized block of imitation cheddar did nothing to hide the item’s odd greasy texture although it did partially conceal how the cheese product appeared to be sweating.

For Alexander Mint’s send-off, there was no caviar (domestic or otherwise) nor the favored Maryland crab balls (although they called them mini crabcakes now since balls had become offensive to some and triggers to others).

At 6:40, as a former prison cook began ladling a lumpy cream sauce atop soggy stalks of anemic broccoli in the Arbor Woods’ kitchen (which was on thin ice with the health department), the guest of honor arrived unnoticed by all but his wife, who clapped.

“There’s my wonderful man,” she called across the lobby and waved in case he didn’t see her, because his eyesight wasn’t what it used to be.

Alexander Mint, in a plain nine-year-old suit, white shirt, and solid mud-brown tie nodded to his wife, because any further expression of emotion could be considered injudicious. Still, he gave her the sort of kiss on the cheek you’d offer your grandmother at a funeral.

“Do you like the banner?” she asked as they stood beneath it.

“I love it,” he said so only she could hear.

“Oh, good.” She squeezed his hand.

He gently squeezed her hand in response and looked into the banquet hall. If he was disappointed by the low turnout, he didn’t show it. The night of Judge Allen’s retirement, a blizzard had been raging outside and there were still four times as many people as tonight.

“It’s going to be a lovely evening,” Dorothy said.

Which was when Judge Mint decided which of his two speeches he’d deliver after dinner.

They entered the banquet room together, holding hands—Judge Mint in his plain suit and Dorothy wearing a dated knee-length dress in a folksy blue botanical print with a belt-square neckline. As notice made its way among the thirty or so lawyers and their plus-ones in attendance, a light round of applause began, although someone called out an enthusiastic, “Hear, hear!”

Judge Mint gave the room an understated wave. If you didn’t know him, at that moment, holding hands with his wife, he would have appeared likeable. But everybody did know him and had been made to endure his pickadilish temperament long enough. But no longer. Hip-hip-hooray. The current governor couldn’t possibly find someone more insufferable than Alexander Mint no matter how many diversity boxes his selection would have to tick.

Sergio Franchi (no relation to the singer, but boy had he tried to establish a familial connection) was the first lawyer to greet the judge, and did so with a Nikon Z 9 he would have never been able to afford had he ignored his parents’ advice to study law or medicine instead of art. (Around the time Judge Mint was appointed, Sergio had been deciding on a college major when his mother showed him an article entitled, How to Make $1,000,000 in Ten Years Taking Pictures Eight Hours a Week, in which the author suggested getting a real job that paid $100,000 a year and taking snapshots on weekends.)

Now the Bar Association’s volunteer photographer, Sergio took a few hundred pictures of Judge and Mrs. Mint with a single press of his finger, a task made simple by his top-end camera having been engineered for far more complex photographic tasks. With a little digital darkroom magic, Sergio hoped to be up to the challenge of improving how the judge gave all appearances of a flounder that had sat for too long in dicey refrigeration. Mrs. Mint, on the other hand, made him think of cherry pie.

With ten minutes until dinner, the county lawyers began making their way to Judge Mint with varying degrees of feigned enthusiasm for the obligatory handshake and farewell clichés.

Except for one lawyer, who remained at the bar and ordered another double. And when the bartender served him and said, “That’ll be ten bucks,” the lawyer replied, “Told you that was my last ten bucks with the last one.”

“Then you shouldn’t have ordered this one.”

Before the bartender could recapture the glass he’d just poured, the lawyer snatched it away and said, “Who died and made you genius?”

The lawyer’s name was Harold Baynes, who when he showed up at every bar association event, lawyers he’d known for twenty years would say, “Nice to meet you.”

While some people, like Judge Mint, imprinted such a visceral reaction it was almost traumatic, Harold Baynes was just the opposite. Harold Baynes could set himself on fire and everyone would forget him before the arson investigators swept away his ashes.

Harold Baynes and Alexander Mint had been in the same law school class. Harold Baynes had graduated with a 3.8 GPA, a solid 1.3 points higher than Alexander Mint. Harold Baynes had an article published in the law review that went on to be quoted in appellate decisions. Harold Baynes had applied for the judgeship Alexander Mint was given.

Since the day he was admitted to the bar, instead of taking a job as an insurance actuary, where he could have worked in the near anonymity befitting his complete lack of charisma, Harold Baynes remained determined to prosper in private practice, and struggled to pay the rent. He was still single. Still lived in the same ground-floor apartment. And had no retirement savings.

That big case never came through the door, and if it had, Harold Baynes wouldn’t have been able to handle it. Not that he wasn’t smart enough, he just didn’t have the means to hire support staff. He tried a few times, but his secretaries always ended up making more than he did.

Those infrequent times when Harold Baynes actually managed to land a client, if he ended up in front of Alexander Mint, he could tell from the judge’s expression he did not remember him. Not just didn’t remember him from law school, but from the last time he was in his courtroom.

For 23 years, Harold Baynes has looked at Judge Mint on the bench and thought: that should be me up there. And although Harold Baynes was not African American, he’d think about the poem Harlem by Langston Hughes.

What does ever happen to a dream deferred?

The gunfire started just as the coral-red sun was setting itself to bed behind a rolling tree-lined hill. Where a corner of the Mints’ farm connected to the Brooks’ farm, a stream ran through a shallow valley of hardwoods, and deer ran along the stream, often doing so at this time of day to flee the high-powered rifle shots and shouted obscenities of Robinson Brooks, who, by conservative estimates, lost $10,000 every summer because of deer eating his corn crop.

Nearby, the want-it-all-now millennials in their million-dollar homes, built on the suburbanized remains of what were once neighboring farms, used to complain about Robinson murdering Bambi, then the deer started devouring all the bushes and antler-shredding the small trees that had been included in their builder’s landscaping package, and the homeowners, while unwilling to pull the trigger themselves, now frequently placed boxes of ammunition in Robinson Brooks’ mailbox.

Milton Weller, surviving spouse of Dorothy Mint’s cousin, spotted the dozen deer 700 yards away, coming up the hill out of the woods that connected two of the county’s last farms standing. Since deer did not bother cattle or eat wheat, Milton didn’t give them a second glance from the air-conditioned cab of his combine. Which was why he didn’t notice when one of the deer was shot although well out of range of Robinson Brooks’ Winchester Model 70.

“I am honored this evening to speak about my dear colleague, Alexander Mint…” So began Judge Prisha Patel’s speech, which everyone hoped would be even shorter than she.

At four-ten, the state’s first Indian-born judge required a small step stool to see over the plywood dais.

Judge and Mrs. Mint sat to Judge Patel’s left. Judge Lee Baek, the state’s first Korean-born judge, and her husband Min-Jun, sat to her right. The county’s other district court judge, Karen Reynolds, born and raised in Massachusetts, was absent.

Judge Reynolds lacked her fellow judges’ sense of obligation and had arranged to be assigned to cover for a judge in a faraway county so she would have a valid excuse to miss this debacle short of sticking one of her grandmother’s old knitting needles into her eye.

Before proceeding, Judge Patel asked, “Can everyone hear me back there?” The question drew an appreciative chuckle, because the judge was making a little fun of herself, as she asked this same question at the beginning of every court session, aware that her soft voice didn’t carry.

“Loud and clear, judge,” Jim Morton guffawed from the back row of tables, where most of the lawyers sat, unheeding Melissa Shore’s urging that the seats closest to the guest of honor be filled.

Only Doug Reed and his tattooed plus-one willingly occupied front-row-center positions and oddly did so with the sort of smiles generally associated with young children on their way to Disneyworld. The other lawyers now unhappily ass-planted in that vicinity were stuck there out of a lack of options due to their late arrival, because Melissa Shore, calculating the turn-out would be even more sparse than RSVPs indicated, had instructed the Arbor Woods staff to haul off any still-empty tables that had been set up toward the back of the room.

Judge Patel, who the old white lawyers in the county inevitably referred to as Ghandi among their own kind, proceeded to offer such kind remarks about Alexander Mint—even getting in a few anecdotes that were miles from the truth—most everyone thought perhaps she was reusing a speech originally prepared for someone else. Or maybe it was a karma thing. Or maybe she was so giddy with concealed glee that she was going to be rid of Alexander Mint she couldn’t think straight.

Bob Gibson, deaf as a stone, perhaps from four decades of partnership with loudmouth Jim Morton, could clearly be heard asking, “Who the hell is Ghandi talking about?”

Tom McMillan, who moments ago thought his throat was closing in protest of the dry hunk of boneless chicken breast no amount of Frank’s hot sauce had been able to rescue, absently made a circular motion with his hand in hopes that might speed up Judge Patel’s pleasantries.

Then it was Judge Baek’s turn and because she came from a culture that took care of its elders, she spoke kindly of Judge Mint, and expressed deep gratitude for all that he taught her and for being so patient with her when she was first made a judge.

And Bob Gibson said, “You think the jokes on us and it’s getting lost in translation?” because Bob Gibson thought anyone who spoke with any accent other than where he’d come from in South Carolina was speaking a foreign language.

Despite her best intentions, however, two minutes in, Judge Baek was clearly running out of steam, so she turned respectfully toward Judge Mint and wrapped it up, saying, “Whenever I needed to know the rules, I didn’t need to open any book. I only needed to knock on your door. Thank you. Enjoy your retirement in peace and prosperity.”

As Judge Baek withdrew from the microphone, an anemic round of applause managed to muster itself into existence but was fading before Judge Patel made her way back to the dais or she may have fallen—no one could see her behind the dais until she got the portable steps back in place and ascended the two risers.

Which was when Doug Reed seized the opportunity to stand and turned toward the restless audience and announced, “I’d like to say a few words about the jurist I admire more than any other. A man who has motivated and inspired my career as a lawyer. A man I have been honored to know and appear before. The Honorable Alexander Mint!”

And Bob Gibson said, “What’s the hippie on now?” Because Doug Reed had long hair that he tied in a ponytail. And drove a Harley to court. And wore biker boots with his suits. And didn’t give a flying flit what the rest of the bar association thought of him. And could try the hell out of a criminal case, often for fees he’d never get paid because his clients were poor. But who for some reason, perhaps only discoverable if offered decades of psychoanalysis, admired Judge Alexander Mint. Despite the fact Alexander Mint hated Doug Reed’s guts.

Judge Mint hated Doug Reed so much that when the ponytailed lawyer started saying the evening’s only truthfully heartfelt words in the judge’s honor, Alexander Mint suffered a momentary blindness that caused him to so abruptly jump to his feet he nearly knocked over his chair.

Dorothy thought her husband might be having some kind of attack.

Forgetting all about the speech he was supposed to make, Alexander Mint let loose with a remark he’d been holding back since Doug Reed first stepped inside his courtroom a dozen years ago. Alexander Mint barked, “Get a haircut, Mr. Reed!”

Which caused the damnedest thing to happen.

Maybe because of the way the words had squeaked out of his throat from the dry chicken, everybody in the banquet hall broke into laughter, thinking Judge Alexander Mint, after 23 humorless years, had made a joke. Including Doug Reed, who clapped his hands above his head and cheered, “Hear, hear, Judge. Hear, hear.”

The only person who wasn’t laughing was Harold Baynes. He might have been had he still been in the room. But upon learning Harold had skipped paying for that second double scotch, Tom McMillan had him tossed out of the building, thinking Harold was a crasher, not someone who’d been paying his bar association dues for three decades.

“What a lovely evening,” Dorothy Mint told her husband. “Happy Judge Mint Day.”

The couple stood in the Arbor Woods parking lot as the final wisps of sunset faded along the horizon.

When he’d arrived three hours ago, Alexander Mint had looked for his wife’s pick-up and parked his eleven-year-old Jeep Cherokee alongside it.

“That was a wonderful speech, Alexander. Wonderful.”

In the end, he hadn’t used either of the speeches he wrote. Not the one that vented his repressed anger at the poor trial practices of the attorneys who’d appeared before him over the years or the gracious alternative about appreciating a career in a profession serving the law, the former of which would have likely emptied the room and the latter of which would have been more saccharine than the imitation Jell-o mold served for dessert.

Instead, Judge Mint spoke about the loneliness of being a judge. How no one treats you the same as they used to, even old friends. How hard it is to rule against lawyers you know, aware they may think less of you, and may even come to dislike you. When all you are doing, as a judge, is enforcing the law you were appointed to uphold.

Which all sounded good and well, except he’d been so bad at it. Although tonight, with him leaving the bench, likely because he was leaving the bench, the air in the room had turned less hostile. Bygones being bygones and all that. And it went both ways. Because when Doug Reed had come to say goodbye, he’d clearly wanted to hug, so Judge Mint allowed that, and Doug Reed actually had tears in his eyes as he whispered to the judge, “Tomorrow morning. Tomorrow morning, first thing.”

Alexander Mint had no idea what the ponytail lawyer was talking about but had patted him on the back and Dorothy had commented, “What a nice young man.”

Which was when Alexander had said, “Let’s go home, Dorothy.” Because he’d started feeling tired half an hour ago.

Now, in the parking lot, as the sun set on Alexander Mint’s last day as a judge, he held his wife’s hand and she asked, “Will you miss it?”

“I expect I will,” was the extent he was prepared to admit, and they left it at that.

They had never talked about this. Their relationship was close but not intimate. Years ago, a girlfriend of Dorothy’s asked what attracted her to Alexander and said it in a way that made it seem improbable she could be attracted to him at all. And when Dorothy had candidly answered, “His low sex drive,” her friend had laughed.

It was more than that of course. But attraction’s magnetism was different for everyone. Not that there had ever been lightning bolts. Dorothy had always been practical above all else. Farming did that to you. She saw in Alexander a good partner. Someone who would help her keep the farm going. It was disappointing none of their children had remained to help run it, but lots of children fled the nest. It was natural they should find their own lives.

Alexander Mint opened the truck door for his wife and said, “I’ll be following right behind you.”

“All right, dear.” Dorothy started her reliable truck and was backing from the parking space when a man emerged from the shadows, and it gave her a start.

Alexander turned and saw the man now, too. Something was in the man’s hand.

“Judge,” the man said. “This yours?”

Seeing the phone Tom McMillan held, Alexander Mint felt his breast pocket. “No, Tom, got mine right here.”

“Wife’s maybe?” the Bar Association Vice-President asked.

“Have your phone, Dorothy?” Alexander called over the low rumble of the farm truck’s engine.

She reached into her handbag and showed him that she did.

“Not ours, Tom. Thanks, though,” Judge Mint said. “For coming out.”

“Yeah.” McMillan nodded, then shook the judge’s hand. “Take care of yourself, Alex.”

“You, too.”

The war was over. No one had won.

Tom McMillan went back into Arbor Woods. There was a card room and he liked to play poker. In a different life, that’s what he would have done for a living. Maybe he could still in this one. One big case—give him one big case and he’d settle it and get the hell out.

Alexander Mint got into his Jeep Cherokee and followed his wife from the parking lot onto the highway. Onto the interstate. Onto the two-lane road that, six miles and two turns later, brought them to the lonely country road that wove through tall pines and oaks which would remain alongside them until the half-mile stone driveway to their farmhouse.

Which was where the brake lights of Dorothy’s truck came on and she stopped in the travel lane. Put on her flashers and got out.

Alexander powered down his window and called ahead to her. “What’s wrong?”

“Deer got shot,” Dorothy called back.

Alexander exited his Jeep and joined his wife in the headlights of her truck, where she knelt alongside the dead deer and placed a hand on its shoulder. A doe, he observed. Two or three years old.

“Still warm,” she said, matter of fact. “Robinson’s usually a better shot,” she said of their neighbor. “Looks like this one got away from him.” She stood to retreat to her truck. “I’m going to call Milton. Have him come out on the Gator. Meat’ll still be plenty fresh.”

“This hour?”

“He’s a night owl. Besides, this is good meat. No sense leaving it to the vultures.”

“All right. I’ll wait with you.”

Dorothy reached into the truck for her handbag, got her phone. “You can go on ahead if you want.”

“You sure?”

She could tell he was tired. “I’ll be fifteen minutes behind you.”

The judge nodded. He was tired, but for some reason, he didn’t want to go up to the house. As if walking inside would mean this day, this evening, this career really was all over.

He was right about that.

On television and in movies, when someone was shot inside their home, the director often framed an exterior of the house, showed a flash behind one of the windows, and provided the crack of gunfire. Or if the actual killing was filmed, the person with the gun would say something to the person about to be shot, like, “If you close your eyes, it’ll make it better.”

But if you actually did it either of those ways, Jake Burton thought, you were doing it wrong.

What you did was: you got inside the house before the person you wanted to kill came home. And you went straight to the medicine cabinet and rummaged through it like a drug fiend looking for a high. Then you dumped out the dresser and nightstand drawers, because that’s where people kept drugs, or money, or guns—guns like the old .32 caliber Smith & Wesson Model 19 Judge Mint kept under the bed in the room where he slept apart from his wife.

Then with that Smith & Wesson in one gloved hand and your own Baretta in the other (in case the about-to-be-victim’s gun misfired), you waited inside the door of the mudroom of the stone farmhouse, and when the person you wanted to kill stepped inside and closed the door behind them, but before they reached the wall switch to turn on the lights, you shot them.

And there was a little flash of light from the end of the .32’s barrel (because it did not misfire, but fired very well), but nothing like they showed on TV. And the sound was loud, but a great thing about old stone houses besides how they held the heat in the winter, was they held sound, too. Not that either the flash or the sound that carried beyond the house was noticed by anyone, because living on the protected slope of a hillside in the middle of 120 acres was good for that. What it was not good for, nor were the surrounding woodlands Jake had needed to trek through, were ticks, which Jake would be plucking out of his Cadillac for months.

Alexander Mint was buried in a cemetery plot overlooking a hillside that used to be farmland but was now a hodgepodge of vinyl-sided tract homes built on the cheap in one of those real estate downturns no one ever thinks will happen again.

There was a large turnout, because the death of a judge was one of those unifying events that brought out the legal community like droves of ants to spilled sugar water. People who didn’t know Alexander Mint praised him (primarily because they didn’t know him) and made up stories of the times they’d appeared before him in court that were told more to venerate the person telling the story than the judge, because that’s just what lawyers did.

Law enforcement made its presence known. Higher ups from the county and state wore crisp uniforms bedazzled with more bars and insignias than a third-world despot, and they adeptly avoided questions from the media about the progress of finding whoever had broken into the judge’s home, stolen some prescription medicines, and apparently used the judge’s own gun to kill him when he walked in on them.

Doug Reed was there, who no one recognized because he’d had his hair cut. No more trademark ponytail, but a slick and swept back style that made him look as if he’d just hopped out of a roadster in Sardinia instead of Harley in Sturgis. Although no one remembered, Doug Reed had applied to be the district court law clerk when he was in his third year of law school, and although Judge Mint had nixed the idea of a ponytailed clerk, Doug Reed, like a child desperately trying to please an unreasonable father, had strived to garner the judge’s admiration ever since.

When the bagpipes started playing, some people managed to cry, although Jim Morton told Bob Gibson he should be glad he was deaf.

Dorothy Mint did not cry, because farmers, like judges, needed to be stoic to survive. Needed to be practical.

Throughout the viewing, service, and burial, Dorothy was flanked by her daughters.

Alice had flown in from Alberta with her petrochemical-engineer husband and four children, who Dorothy had only ever seen in pictures. The grandchildren, aged 5 to 11, didn’t know what to make of so many people gathered to honor a man their mother had always described as being rotten as a wormy apple.

As for their grandmother, the kids liked her right off, the way she smelled like the outdoors and hugged them like she really loved them and seemed to know all about them. When they asked why she never came to Canada, she answered because she had to take care of the farm, which didn’t make sense to any of the kids until they saw it.

Alberta had lots of open land and farms, but Alice and her family lived in a suburb close to the city to make her husband’s commute easier, and while they spent a great deal of time outdoors, it was typically at the area’s many trails and parks, not the farms they only ever saw from car windows.

All four grandkids said they wanted to learn how to milk a cow, and Milton, who had been there when Dorothy had shown them around, said he’d teach them.

Dorothy’s youngest, Penny, was good at being the cool aunt to her sister’s children and tended to act more like they did than her older sister. But Penny had always been that way. Dorothy never met either of Penny’s now-ex-husbands, but from their pictures assumed they were as untethered to the prospective burdens of responsibility as her daughter. Which there was nothing wrong with, provided you didn’t need to run a farm. Which Penny never had any interest in.

Alexander Jr.—the sting of Junior Minty forever tattooed to his psyche—remained in Japan. When Dorothy called to tell him his father was dead, he didn’t say he was sorry, only that he would never come back. She said she understood but hoped one day he’d change his mind, and if he did, she’d be happy to see him. But she knows he will never return. And she will never see him again, because she will never travel to Japan.

She will never travel at all. She will happily live out her life at the farm. At this farm, where she was that night, with the judge in the ground, and her daughters and four grandchildren and son-in-law tucked into beds in rooms her girls hadn’t slept in for years.

Over the next few days, Milton will show the grandchildren how to milk cows, and Dorothy and her daughters will go through Alexander’s belongings, and bag his clothes for the charity shop at Dorothy’s church, and box up the papers Alexander kept in his office, which Alice’s husband will say they should have shredded and not just take to the landfill.

Dorothy will tell him that’s a good idea, and not suggest just burning the papers, which is what she did with the handwritten notes and research she found months ago when Alexander left them out on his desk in his bedroom. Notes about how Alexander was working on legal arguments to get the farm out of the preservation program so it could be sold. Because a developer had presented Alexander with a Letter of Intent confirming he would pay $12 million for the land. $100,000 per acre.

The afternoon Dorothy found those papers, she wondered what Alexander was thinking, because he had to know there was absolutely no way she would ever sell the farm. And Alexander had no power to sell it himself because the deed was in her name only. Her father had seen to that. There was only one way Alexander would ever own the farm, and that was if she died before he did… If she died first… If she was dead… And with thought, she heard crows squawking warning outside.

Which had caused Dorothy to think back to when she was a young woman and had gone to the State Fair where a gypsy girl (what they called them then) told fortunes in a tent.

Dorothy’s friends made fun of her, and said the whole thing was a scam, but Dorothy wanted to do it, so she went into the tent and met the gypsy girl who was so short Dorothy thought she might have been a child but found out they were close to the same age.

The girl was pretty and had long dark hair. She read Dorothy’s palm and told her she saw that Dorothy lived on a farm, and that she was an only child, and that she worried about being able to run the farm when her parents got too old. But the girl told Dorothy not to worry. She was going to meet a man who would marry her, although he would not love her, and she would not love him, but he would give her three children and he would help her keep the farm. But he would not do that forever, the gypsy warned.

When Dorothy asked what that meant, the mysterious dark-haired girl shook her head and said, “I’m not sure. But when that day comes, you’ll find me and maybe then I’ll know.”

“But how will I find you?”

“You’ll remember my name.”

“I don’t know your name.”

“My name now doesn’t matter. When you need to find me, I’ll be Miss Vicky. That’s what the sign will say on my front yard. I’ll be living in a little bungalow with my son, whose name will be Loiza. And Loiza will work with a man who will help you.”