“Seems unscrupulous, doesn’t it?” Loiza asked Jake, who didn’t reply because he wasn’t sure what his young helper was referring to, which was nothing new.

The generational divide, being what it was, sometimes made Jake’s native English language seem as foreign as many of the faces he now encountered every day. When he was growing up, his neighborhood had been mostly white, black, and a handful of Asians—the latter of whom he used to associate with running carry-outs or dry cleaners, back when people only ate out occasionally and dressed up to go to work. Generational divide again.

Perhaps when handsome Loiza was in his 50’s (as Jake was) he’d be equally as confounded by people three decades younger (as Jake was).

“Poison…” Loiza detailed, presumably continuing his thread about unscrupulousness. “Have you ever poisoned anyone?” he asked Jake.

“No.” Jake omitted the additional detail that he wouldn’t know how. The primary tools of Jake’s profession were handguns and bullets. Occasionally a heavy length of pipe entered his repertoire, usually because some glitch had undone the general effectiveness of bullets, which, from Jake’s experience, were a reliable means to kill someone, assuming you fired them from a weapon with reasonable aim and didn’t throw them—which, growing up, Jake would have assumed everyone knew.

Now … Jake found it nearly impossible to take for granted anyone’s understanding of what he believed to be common knowledge: such as restaurant coffee being served piping hot, which required reasonable sipping to enjoy as opposed to unfettered gulping and filing a lawsuit for a scalded tongue.

“It’s also sneaky,” Loiza believed, still referring to poison as a means to kill someone, Jake assumed, more particularly to kill Nelson Thackery, who Loiza and Jake were watching from Jake’s Cadillac.

They were parked in early-evening darkness in the wide alleyway that ran behind the tiny rear yard of Nelson’s circa-1940 rowhouse and the blocks-long row of identical houses on the next street over.

It was—relatively speaking—a safer section of the city, which, along with the brand and newness of Jake’s sedan and the presence of a few other like-parked cars, prevented their continued presence from arousing suspicion despite the vehicle’s tinted windows. Presumably, they were just another local resident who preferred parking off travelled streets. Or they could be visiting a patient at nearby Union Memorial Hospital, where Nelson and his yet-to-arrive date would likely be pronounced dead later that night if Nelson uncorked that bottle of Nebbiolo and served it along with the beef Bolognese he’d been cheffing over for the past two hours.

Nelson had carefully selected the robust Italian wine after a time-consuming Google search keyworded with “pairing”, “beef Bolognese”, and “under $40”—which said bottle, subsequent to Nelson’s purchase, had (according to Loiza’s source) been expertly tampered with by Andrey Molikov, who had artfully uncorked it, gently stirred in a deadly tasteless liquid of his own proprietary chemical creation, then reinserted the cork and applied a splendid forged capsule.

It was Molikov’s intention that the now expertly spiked wine, within hours of ingestion, would bring upon death(s), whereupon Molikov’s chosen weapon—poison—given the overworked atmosphere of most city pathology offices, was unlikely to be spotted, leaving homicide detectives (assuming the death(s) were deemed suspicious enough to have summonsed them in the first place) scratching their heads as to whether it was murder, and wasn’t it simpler to simply call it carbon monoxide poisoning, these old rowhouses being what they were, despite any evidence Nelson Thackery’s house suffered from a faulty air exchange system? But you had to fill in something on the reports, otherwise it looked bad from a statistical point of view.

As for Loiza’s protest about poisoning being sneaky, Jake wasn’t sure why that would be objectionable, as a crucial element of a successful career in the killing business was getting away with it. One-hit-wonders may have been a way for rock bands to enjoy a comfortable lifetime of royalties, but it didn’t work that way in the murder-for-hire gig.

“Poison does seem very Russian, though,” Loiza continued to philosophise in his youthful manner, being at that age when so much life was presumably yet to be lived it allowed for the luxury of idle pontification. “You set the poison,” Loiza concluded, “and you can be thousands of miles away when it does its job. Although not Molikov.”

No, not Molikov, because according to Loiza’s friend in China, Andrey Molikov was not only a brilliant chemist, assassin, and spy, but quite the sadist. Molikov liked to witness the demised fruits of his deadly work-product firsthand. Which meant (again, according to Loiza’s friend in China) Molikov was nearby.

“Guns, though,” Loiza went on to suggest a moment later and with an appreciative nod, “are very American.” He said that in the proud tone used by many first American-born children of immigrants when speaking of their family’s new home country. “Guns,” Loiza repeated with robust approval, “are right there. In your face.”

Or the back of your head, Jake was about to reply, but, as often happened in these one-sided conversations with Loiza, he remained quiet, continuing his observation of Nelson Thackery, who stood behind the kitchen window at the rear of his narrow brick home and once again—perhaps obsessively—tasted his Bolognese, failing to appreciate a Russian assassin intended to kill him and was likely lingering nearby awaiting to enjoy the process.

“The English…” Loiza further considered, “…now I don’t think they’re into guns. I picture them going more for murder by hanging … maybe a candlestick—something very Clue-y.”

Jake could see that.

“Germans…?” Loiza thoughtfully self-proposed. “Machine guns. Like in those World War II movies—rat-tat-tat-tat-tat.” Loiza pantomimed firing a stockless MP-38. “Italians on the other hand…?” He thought a moment before suggesting: “I think car bomb. The French would be guillotine. And the Japanese: sword—big samurai sword. While all of Southeast Asia would be machete. The Chinese, though, maybe torture—pulling off fingernails … something like that. Closer to home, Canadians…? I don’t know … bear trap?”

Loiza’s global murder weapons tour was interrupted when his right earbud relayed the sound of Nelson Thackery’s doorbell. “Girlfriend’s here,” Loiza reported, checking Nelson’s doorbell camera to find Ellen Ambrose, a 37-year-old financial advisor, giving her cashmere sweater a gentle tug at the waist, a gesture that was more anxious tic than actual adjustment to the lay of the soft fabric.

Ellen wasn’t Nelson’s girlfriend as Loiza stated. Her relationship with Nelson was still in the getting-to-know-one-another phase, as this was about to be Ellen’s first entré into Nelson’s home as well as her initial opportunity to experience his cooking. All of which she held in high hopes, because Nelson (so far) didn’t seem needy, owned his own home, and apparently knew his way around a kitchen, although this job of his (freelance reporter) seemed unlikely to bring in the sort of financial-wherewithal that would whet the investment-advice appetite of the firm where Ellen was a sixth-year associate with partnership aspirations. But give a guy a chance—which was what this dinner was all about.

Dinner was actually about much more, but Ellen was without reason to appreciate that. In fact, Nelson wasn’t up to snuff on the topic either, not realizing just how big a story he was on the verge of breaking … and if that bottle of vintage “Andrey Malikov” did its job, he never would.

Loiza continued to watch the night-dimmed screen of his laptop, having hacked into Nelson’s home security system. He observed Nelson remove his apron and walk briskly to the front door, where he greeted Ellen with a welcoming smile. The two of them were tentative but eventually shared a non-amorous hug in the small foyer before Nelson led her to the kitchen, where Ellen happily complimented, “Smells wonderful.”

As Jake looked around for the Russian killer, Loiza asked, “What happens if they open the wine before Molikov shows?”

Jake had been wondering how long it was going to take before that came up.

When Jake didn’t respond, Loiza sighed, “I was afraid of that.”

Nelson and Ellen settled in the living room, where she remarked glowingly about the exposed brick wall and the impressionist oil painting by a local artist which hung there.

The living room, softly lit by recessed lighting, was open to the kitchen and small dining room thanks to an HGTV-inspired reno five years ago, when, thankfully, the then-owners retained the original hardwood floors despite numerous gouges, stains, and dog claw marks, appreciating even marred wood was far more lux than “luxury vinyl flooring”, which any designer worth their NCIDQ should tell you is a misnomer.

Nelson served a simple antipasto of which the black olives and fresh mozzarella were the stars—ingredients he selected just that morning at Trianacria. He and Ellen nibbled in the mannered way of two potential lovers not yet comfortable enough with one another to reveal any tendencies to gluttony. As an Internet researched beverage accompaniment, Nelson had stirred up a pair of orange spritz aperitivos—orange soda (aranciata), prosecco, and Aperol—which did indeed make for a bright, citrusy cocktail.

They were joined in the living room by Nelson’s overweight corgi, who Nelson released from the spare bedroom where he’d enclosed him upon Ellen’s assurances she was fine with dogs, although from the awkward way she petted the calm animal between its perky ears—more tapping with her fingertips than fond stroking—Loiza could tell she was just being polite and would have preferred Nelson to be dogless.

To Loiza’s relief, the poisoned bottle of wine remained in the kitchen. Loiza wasn’t looking forward to sitting idly by while two people were poisoned to death, which seemed to be Jake’s plan to bring Molikov out into the open to kill him since Loiza hadn’t come up with an alternative.

Until today, Loiza’s main lead to locating the homicidal—not to mention unscrupulous—Russian had been a mobile phone number provided by Loiza’s same friend in communist China who, just last week, suggested this evening’s exercise in capitalist earning in the first place.

Jake’s initial response to the plan had been a solid no, but with Grace in his ear he’d ultimately agreed.

Grace, the love of Jake’s life, often allied with Loiza in matters such as this and since she frequently encouraged Jake to be open to change and new opportunities, he figured this plan certainly fit that definition. He’d signed on despite the need to rely on information provided by someone in China who: (a) he had never met; and (b) Loiza had only ever dealt with on something referred to as the dark web (which was another of those terms comprised of English words which Jake understood individually but not when paired together).

As for Molikov’s mobile phone, Loiza hadn’t come across any indication it was still live, although in the process of looking he’d uncovered information which led him in a few other directions, however none of those hacker-centric leads panned out beyond: (a) a poorly-focused three-year-old FBI surveillance photograph of Molikov; (b) a dated NSA file note that indicated Molikov preferred to drive Subarus; and (c) far more current intel—again from his friend in China—that Molikov had tampered with Nelson Thackery’s bottle of wine at some point in the past five hours with the intention of said substance bringing about Nelson’s demise tonight.

Growing anxious, Loiza began to bounce one leg, which caused his laptop to dance on his lap.

Loiza’s electronic visage was a split screen. On the left were live images from Nelson Thackery’s home surveillance cameras, including a dog cam, which Loiza could control, widening the angle and roving the camera eyeball to follow Nelson and Ellen—although that electronic adjustment, while apparently unnoticed by Nelson or Ellen, alerted Chamberlain the corgi, which caused the dog to inquisitively put his nose to the knee-high-mounted camera and stare into the lens, partially blocking Loiza’s view until Chamberlain wandered back to the coffee table to beg more olives (and while such hungry conduct was a generally common canine tendency, it was especially unsurprising given how Chamberlain’s paunch was already buffing the hardwood floors as he proddled from treat to treat).

On the other half of Loiza’s screen was a cryptic flow of unintelligible letters, numbers, and symbols eagerly seeking clues as to Andry Molikov’s location. Jake was attempting the same thing by looking out his Cadillac’s windows.

Inside Nelson’s house, Ellen asked her host if there were any developments with the story he told her about the other night, which she said sounded fascinating, although she said that in a hospitable tone that may have just been being kind. Ellen was interested—just less in terms of whatever Nelson was investigating and more as to indication of its income-producing potential. Not that relationships were all about money … but let’s be frank, it helped.

Nelson was only too happy to oblige, his chitchat speech cadence shifting gears to a level implying greater importance, as if he was giving one of those less-lecture-y TED talks. He sat up straighter on the three-cushion sofa, perhaps making room for his diaphragm to project to the back row.

“All around DC,” Nelson began, key to set his story’s hook, “there are all these fired private contractors. They’re everywhere. And it’s not just last-hired first-fired. Career contractors are being let go. DOGE fatalities. The streets are littered with them.”

Listening in on the conversation, Loiza thought Nelson would be better served getting to the point without descriptions like “streets littered with people”, because were they really?

Ellen, meanwhile, made a sound something like, “Mmm,” apparently feeling the need to show appreciation for Nelson’s enthusiasm, although she wasn’t sure exactly what a “private contractor” was, and that seemed key to Nelson’s story. She had been briefed about DOGE at one of her company’s breakfast meetings, but that had been in preparation to show due sympathy should any of the firm’s clients be laid off and contemplate withdrawing funds from their account to live off of, which would be ill-advised, or so her fellow financial advisors were schooled to advise.

Nelson stressed, “Tons of these fired workers have high security clearances. Super high. Almost White-House-level high. And like that,” Nelson snapped his fingers, “they’re out on the street. Lots of them got let go by email. No warning. Skimpy severance packages. And … they … are … pissed. Really pissed.”

“I guess so,” Ellen appreciated, although she wasn’t sure about the repercussions of a security clearance, and given the emotional immaturity of a couple clients she’d worked with who reportedly had such clearances, was it that difficult to obtain one?

“And none of this,” Nelson informed, “is lost on the international espionage community.”

“You mean spies?” Ellen asked, intrigued by intrigue.

“Mainly we’re talking analysts. Intelligence analysts. Thousands of them laid off. More every day. In some cases, they’re no sooner out on the street than they’re approached to sell information about what they’ve been working on.”

Ellen wondered why she hadn’t been more into this the other night. “Sounds like movie stuff.”

“It’s crazy what I’ve gotten so far. And I feel like I’m just scraping the surface. So far though, the laid off contractors I’ve talked to … none of them will go on record or say who whoever approached them is working for. Could be competitors—you know, other companies. But one woman’s pretty sure she was contacted by a foreign government because the guy offered to relocate her out of the country. Which could mean an enemy—Russia … Iran. But this woman said friendly governments run espionage projects, too. And the amount of money they’re being offered…” Nelson sat back and raised his hands as if unleashing an explosion while making a corresponding sound effect, something like, “Pwwooosh.”

Which Loiza didn’t think sounded like an explosion at all, as he reported to Jake: “He has no idea what he’s onto. Nelson,” Loiza specified when Jake looked over at him. “No idea.”

What Loiza meant was that what Nelson didn’t know, but was a few well-placed questions to the right DOGE-fired contractors from finding out (presuming he didn’t drink that poisoned wine) was what Andrey Molikov and his many, many, many multi-national brethren did know: which was that state secrets were getting cheaper by the day, marketplace wise. In fact, the offering price for high security secrets wasn’t just failing to keep up with sticky inflation but dropping like a stone, as the number of embittered laid-off high-security-clearance employees continued to rise, increasing the supply side of the economic equation.

Nelson wasn’t alone in this regard. The DOGE hatchet men handing out pink slips like Halloween candy were clueless that the bulk of intelligence analysis was not done by the NSA or CIA but by private contractors whose contract terms gave all appearances that they were doing trivial and redundant work, which was part of the deception of their craft. Only the deception was so well planted it easily convinced the eager just-on-the-job job-choppers they were eliminating waste when they were, in fact, dismantling critical intelligence systems that had taken decades to conceal, but, oh well, to be able to say you witnessed the end of the world surely had to give one some street cred, history of civilization speaking.

And it wasn’t just the Russians scouring the marketplace, but the Chinese, North Koreans, Iranians, pretty much anyone interested in obtaining military secrets, which was pretty much everyone, which had increased the number of foreign agents now running around DC to the point it was almost impossible to get a decent hotel room without driving all the way out to Leesburg (which did have good outlet shopping and a great hamburger place called Melt, so that was a plus).

All of which was why Nelson Thackery had to die before he discovered and then spilled these beans, be it to a magazine, news agency, or his own blog. At least that’s how Andry Molikov’s bosses saw it.

What Jake said, not necessarily in response to Loiza’s observation, was, “Subaru.”

“What?” Loiza asked, not having heard Jake for concentrating on Nelson and Ellen’s conversation, because the pair (still too early to refer to them as a couple) were moving into the kitchen, closer to opening that bottle of deadly wine, Loiza feared, while Chamberlain the corgi rued that the shortness of his legs prevented him from reaching farther onto the coffee table where the unfinished plate of antipasto remained.

“Subaru,” Jake repeated, and pointed through the windshield at the dark WRX that just drove by in the alley and was now pulling over to the side a few parked cars ahead, idling a moment before its lights went out.

They waited to see who exited the vehicle. Saw no one.

“Molikov?” Loiza asked.

“We’re about to find out.” Jake opened his driver’s door, wearing a dark sports coat, dress shirt, dark trousers, and black Amberjack dress shoes with soft soles (comfortable and quiet {Grace found them for him online}). Jake’s sports coat was unbuttoned. One gun was holstered under his left arm, two more—one on each hip—on his belt. Things went really bad, he had a fourth gun holstered around his left ankle. The arsenal was four times his usual quantity—because of the target.

Loiza anxiously ran a hand through his hair, checking for witnesses as Jake stealthy approach the Subaru.

The alley remained quiet. Of the dozen rear windows with a view of their position, only four—including Nelson’s—had any interior light showing. In the 45 minutes they’d been staked out, only two cars (not counting the Subaru) had driven by. One woman had emptied a vacuum cleaner bag into a trash can. And a rangy mutt had sniffed then lifted his leg on a different trash can—pee-mail.

Loiza watched Jake weave casually between parked cars, taking a quick glance inside each with the narrow red beam of a night flashlight—as if he wasn’t a hitman, just your average well-dressed car thief looking for an opportunity.

Nearing the WRX, Jake could see through its rear window: outlines of seat headrests silhouetted against the amber glow of a streetlight, but no heads. When the car had driven by, he’d only gotten a glance inside, saw a driver, no passenger upfront. Hadn’t seen anyone in the back but couldn’t be sure.

Staying tight alongside a large SUV parked directly behind the Subaru, he came up on the WRX’s driver’s window, slid the gun out of his shoulder holster, held it just behind his right hip, finger on the trigger, a lucky 13 rounds in the slide, one in the chamber. Wouldn’t be much time to make a decision to fire. If Molikov had a doppelganger, the lookalike was about to wish he looked like someone else.

When Loiza lost sight of Jake behind the big SUV, he eased open his door and listened for the telltale quiet whoosh of silenced bullets being fired and spent shell cases clinking onto concrete. But instead, he heard quiet footsteps.

Jake came quickly down the alley, head swivelling methodically side to side, looking around as he got back into the Cadillac. Pulled shut the door. “No one in the car.”

Loiza squinted in surprise, about to ask how that was possible when Jake continued:

“Either he got out the passenger side. Or he’s modified the car and got in the trunk through the backseats and is still in there.”

Either way, Loiza realized, it was suspicious, which caused him to conclude, “Molikov.”

Jake started the engine and shifted into reverse, backed from where he’d parked.

“What are you doing?”

“If it’s Molikov, he’s probably spotted us. Even if he doesn’t guess why we’re here…” Jake drove forward, continuing to scan the alley as he passed the WRX. Near the end of the block, he said, “What’s going on inside the house?”

Loiza refocused on his laptop. The dog cam didn’t rotate far enough to provide a view into the kitchen, so he could only listen. “She’s asking if she can help—toss the salad. He just asked if she likes wine.” Loiza waited to overhead the response, then sighed, “Yeah—she does.”

Jake turned onto a side street, eyes still scanning. “If you try to warn them about the poison…”

“I know,” Loiza responded with reluctance.

“Who’s to say Molikov doesn’t have his own ‘you’ doing the same surveillance,” Jake reasoned. “You spook him off, where’s that leave us?”

Loiza nodded, which any first-year law school student will tell you is insufficient to establish acceptance of a contract term.

Jake turned left onto the one-way street that would take them back in front of Nelson Thackery’s rowhouse. Traffic was light, only one other car in the same block.

Loiza abruptly sat forward, pointing, “Up there, up there. Five houses from the end.”

A man, wearing black pants and a dark turtleneck had his back to them as he leaned forward, handing something to a homeless guy camped out on the marble front stoop of a house for sale across the street from Thackery’s.

Jake slowed and Loiza tried to get a better look, turning in his seat. “Molikov. It’s Molikov.”

Jake was less certain.

“Same hairline, Jake. Wide widow’s peak. It’s him. Let me out.” Loiza shut his laptop and grabbed the door handle.

“What’re you doing?”

“I’m gonna follow him. You park the car, come find me. You gotta get this guy, Jake.”

“Wait ‘til I’m around the corner. Don’t let him see you get out.”

“All-right all-right.”

Jake made the turn, checked his rear-view mirror to make sure they were out of Molikov’s—assuming it was Molikov—sight line. He no sooner applied the brakes than Loiza was out, hustling back toward the cross street.

Jake continued halfway down the block and pulled into an open parking space. Out of the Cadillac, checking his surroundings, he strode deliberately toward the corner he’d just driven by, no sooner clear of it than he muttered, “What’re you doing kid?”

Across the street and five houses down, Loiza was turning in place on the sidewalk. It couldn’t have been more obvious he was looking for someone than if he was starting a game of hide ‘n seek.

Molikov was gone.

Loiza trotted over to the homeless man slouched on the polished stoop. Slightly winded, he asked the multi-jacketed man if the mini he was unscrewing was from the guy in the turtleneck. “Russian fellow?” Loiza specified.

“What’s it to you?” the man asked.

Loiza didn’t answer that question but pointed instead to the now uncapped mini and critiqued, “That’s not the good stuff.”

“It’s good enough.”

Loiza looked around again for Molikov, no idea where he’d gotten to so quickly. He squatted next the unshaven man. “No, let me get you the really good stuff.” He figured Molikov unlikely to be charitable, and that the contents of that plastic miniature was laced with some new recipe he was trying out. “Get you two of them you give me that one.”

“What’re you talking about?”

“Come on, man,” Loiza stressed anxiously. “I’m trying to help you. Give me that one, I’ll be back with two of whatever you want. Liquor store right there.” He pointed to the corner.

The homeless man tried to remember the last time anyone helped him. A run of shit luck can turn you cynical like that. But he handed Loiza the mini. “Look like you need this more than me. Bad for you.”

Loiza took the tiny bottle and dumped the contents onto the sidewalk as he ran for the liquor store.

Jake was back in the alley behind Nelson Thackery’s house, making his way toward the Subaru. He had his red flashlight out, shining it inside a late-model Corolla but watching the shadows for Molikov, peering over waist-high chain-link fences into the tiny backyards of connected rowhomes—some of the yards nothing but poured concrete, no grass, nothing to mow.

Through Nelson’s kitchen window, Jake saw the freelance reporter uncorking a bottle of wine.

Loiza, at the liquor store front counter, got two minis of Jack Daniels No. 7 and one of those overpriced half-wilted flower bouquets with soft stems that drunks think will get them some forgiveness from whoever made the bad life choice to get involved with them. The flowers came with a blank card—fill in your own schmaltz. Loiza used the cashier’s pen without asking. Paid in cash and didn’t wait for change.

Back on the street, Loiza ran to the homeless guy on the stoop, handed him the two Jack minis.

“Flowers not for me?” the grizzled guy called after Loiza, who ran down the block.

“I thought at first was bear,” the voice said behind Jake. “Big city bear looking for food in cars… Or looking for me.”

Molikov.

Jake had no idea how he’d gotten behind him. Where he’d been in the darkness.

In the same situation, Jake would have said nothing, just started shooting. Maybe Molikov wanted to confirm Jake was looking for him, maybe to find out why.

Jake feinted toward the center of the alley, then dove between parked cars, rolling as Molikov started shooting, silenced bullets popping holes in car bodies and splintering windows.

Jake fired back underneath a Chevy Malibu, his own quiet shots aimed at scampering feet, putting three slugs into cheap tires that started going flat before he got lucky with his tenth shot that caught Molikov in the ankle. The impact of bullet to bone half spun the Russian in place and brought him down, and there, on the other side of the Malibu, was Molikov’s face, and there was his gun in his hand, which he brought around toward Jake, who still had four bullets left—three in the slide, one in the chamber. He only needed the one.

When Nelson Thackery answered his front door, a tall good-looking guy in his 20’s—was he mid-eastern? Slavic?—handed him a bouquet of scrungy flowers into which a small card had been stuck.

Handwritten on the card in large letters were the same words the delivery guy whispered to Nelson: “Don’t drink the wine. It’s poisoned.”

Nelson was too stunned to be afraid—that would start in about 15 minutes, and really take hold once police set up a crime scene in the alley behind his house.

Nelson’s frightened neighbors gathered outside to learn someone had been gunned down, and that there were at least 20 shell casings in the alley and close to that many holes in a couple cars, only no one had heard a single shot.

By the time the police determined the dead man had no ID on him and that his fingerprints had been chemically removed, Jake and Loiza were comfortably miles away.

Loiza was in the basement of the little Rosedale cottage where he lived with his fortune-teller mother. Seated in front of an impressive bank of computing power, the screens of which provided the cellar’s only current light, he ate a sliced apple along with spoons of homemade peanut butter bought from a cute girl he met at a farmer’s market.

Loiza had already wiped any home, business, or government security systems of video that might have included: Jake and his drive to, from, and around Nelson Thackery’s neirhborhood; Loiza’s exchange with the homeless man; Loiza’s time inside the liquor store; Jake going on foot into the alley; Jake’s shootout with Molikov; Jake exiting and meeting up with Loiza on the street, where Loiza had uncharacteristically reacted with a celebratory fist pump, and given Jake a hearty pat on his broad back, which seemed to startle him.

What Loiza was doing now, in digital concert with his friend in China, was diverting nearly half a million dollars from the now late Andrey Molikov’s slush fund which had been earmarked for payment to recently fired private contractors who, abused by their own government, were being shown great love and appreciation by Mother Russia—Andry having had some initial success in said efforts by employing the phrase, “Now who’s your enemy?”

It was a calculated risk that Molikov’s handlers wouldn’t come looking for whoever killed their agent and took his money, but China didn’t think so, taking the position that the Russians weren’t known to be sentimental about fallen agents, tended to blame them for getting killed, and were more prioritized about putting a replacement in place.

Jake, meanwhile, was settled in the cozy living room of his old, restored cottage house not far from the center of the city. It always felt so quiet there, buffered from traffic and people and their collective noise by taller buildings and the home’s thick, stone walls.

Jake was in his favorite chair—the broken-in recliner his father used to sit in that Grace had rebuilt and reupholstered for him soon after Jake made the deal that released her from prison for killing her abusive husband, and she moved in with Jake.

Grace was on the sofa with a knitting light around her neck, cussing under her breath as she continued to try to teach herself the needlework her grandmother used to make look so easy.

An audiobook played at low volume through a set of shelf speakers. Jake couldn’t tell you what the book was about for a million dollars. He wasn’t much of a book person, but Grace liked them. In prison, her cellmate used to read to her at night, and she continued to find comfort in that. Jake found comfort in her.

He closed his eyes and began to doze when his phone pinged with a text.

Jake’s bank in Singapore confirmed $163,174.33 had been transferred into his account. It was his third of the Molikov money, split equally with Loiza and someone in China.

“We could take a trip,” Jake offered Grace over the pleasant narration of the audiobook.

“Or stay here and do nothing,” Grace happily suggested as an alternative. Which was more than fine with Jake.

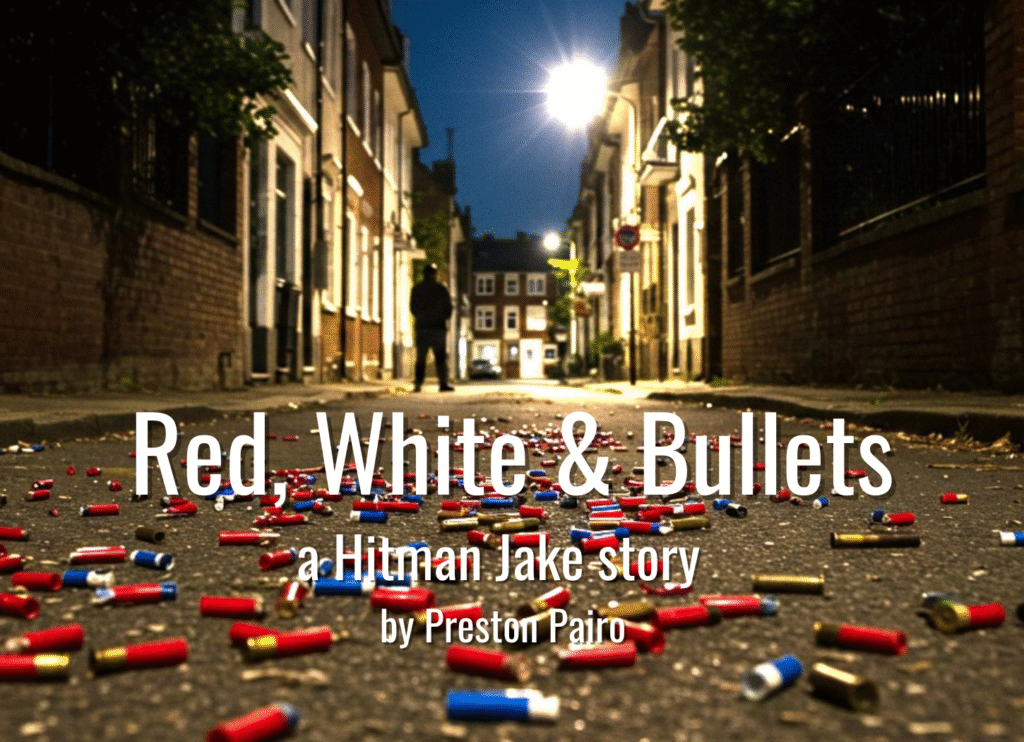

For more Hitman Jake stories, check the table of contents page.

If you think rich people live fascinating lives, wait until you see how they solve a murder (or two).