Normally, Jake didn’t pay much attention to the holiday season other than how the Christmas spirit might impact the difficulty of killing someone he’d been hired to remove from the roster of the living.

It could be a busy time of year. For while Christmas was a source of murderous motivation for some, December 31st generally offered even greater impetus for a fed-up person to resolve they’d had enough already and let’s start off the New Year with a literal bang—as in the crack of gunfire Jake would aim at whoever they wanted dead. Sometimes turning the calendar page to a fresh year made for a tipping point.

Grace, however, loved Christmas. And since Jake loved Grace, he found himself in a festive mood these days—maybe not like when he was a kid, 40-plus years ago, but when was the last time he caught himself humming Andy Williams’ “The Holiday Season”? That song was on the first LP Jake’s mother used to put on the turntable at Thanksgiving, the date that kicked off his family’s Christmas season. Jake’s parents would reminisce about old family traditions, such as standing in line for Rheb’s candy and driving by Edmondson Village Shopping Center to look at all the trees covered with bright strings of lights and the oversized Santa perched atop a make-believe chimney at Hutzler’s department store a few miles farther west.

After Jake’s father was shot dead during a mugging, Christmas was never the same.

Now, humming “The Holiday Season,” Jake experienced a bit of that childhood warmth, which perhaps hadn’t been lost to the shadows of killing people for the past 30 years after all, but merely gone dormant, like a forgotten tray of amaryllis bulbs brought out of the cellar.

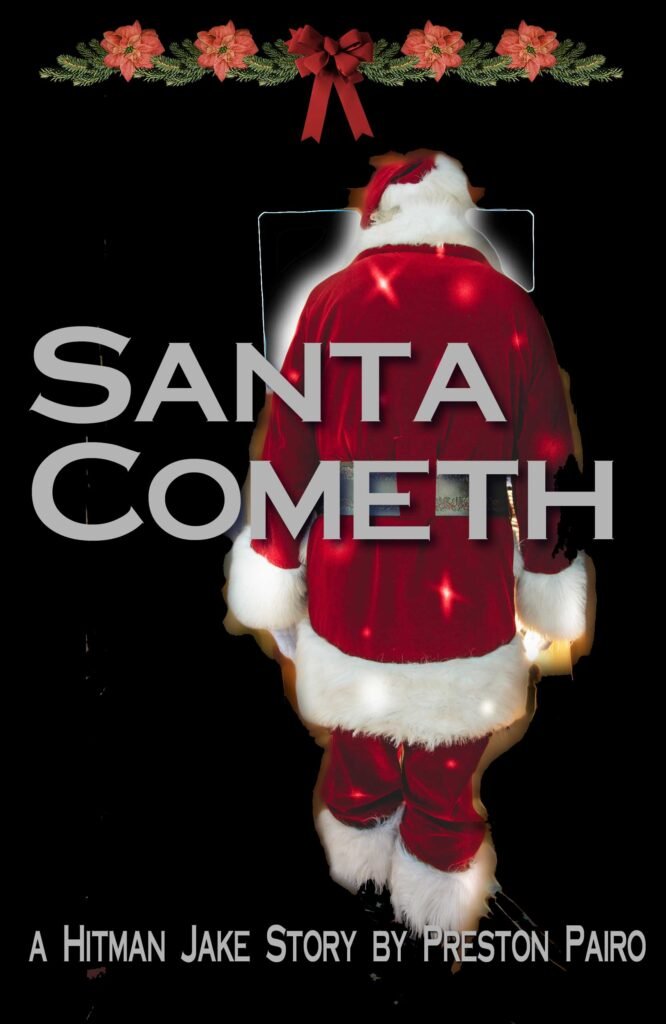

Loiza, Jake’s handsome millennial assistant, found this change in Jake amazing, although he was careful not to mention it and firmly suppressed the urge to smile, even now as—unimaginable as it was—he felt as if experiencing a true holiday miracle: Grace was fitting Jake into a Santa Claus suit.

Ho-unbelievably-ho.

If Loiza ever doubted Jake would do absolutely anything for Grace, this seemed to etch that point in amorous stone. Although whenever Jake had made that proclamation, it was in the context that he’d kill anyone for Grace, such as her abusive husband, who Jake would have gladly filled with bullets, but who Grace had ended up killing before she ever met Jake. At least Jake had worked a deal that got Grace’s manslaughter sentence reduced.

And now here they all were, in Jake’s carriage house in downtown Baltimore, Christmas music playing on Spotify through portable speakers Loiza had set up for them, while Grace did some hand-sewing on the Santa suit.

It was late afternoon, a crisp December day. Grace had a beef stew simmering on the 70-year-old Magic Chef range that had enjoyed a long life because Jake never used it before Grace was released and moved in. There were electric candle lights at all the windows and a decorated tabletop tree in a corner of the kitchen, next to the brick fireplace where a trio of stockings hung from the mantle. They all had a glass of eggnog Grace had sprinkled with nutmeg and adorned with a cinnamon stick.

The Santa suit had come into the house because one of the other cons Grace had served time with had intended to have her wide-girth boyfriend play Saint Nick, but there were warrants out on him, and the cops were being unusually persistent about tracking him down. So Grace had asked Jake, “Would you please?” and he’d firmly shook his head no, but heard himself say, “Sure. Anything for you.”

Jake’s barrel chest may have been full-on Santa proportions, but his belly wasn’t quite up to bulk, and the pillow stuffing Grace had sewn into a cummerbund still wasn’t enough, so she needed to take in a couple inches at the waist of the red suit. The soft fabric smelled a bit of marijuana—an element contributing to the warrants for her former jail mate’s boyfriend—but Grace planned to put sachets of cloves in Santa’s pockets if the odor didn’t dissipate before Jake’s upcoming performance at the community center.

Sitting at the kitchen table, Loiza put on the Santa hat Jake was yet to don and took a selfie he no sooner posted to one of his Instagram accounts than his numerous admirers began responding with loving praise—at least Jake assumed it was praise. No one sent actual words, just little cartoon images Jake had been repeatedly told were called emojis. Jake found emojis ridiculous, but Grace said that’s because he was old. (When he reminded her that he was still on the light side of 60, Grace replied that, in technological years, he was a relic.)

Loiza’s Santa-hat pic taken and posted, he no sooner set his phone on the linoleum table than it buzzed angrily. And Loiza sighed. Because that particular buzz was associated with only one of his contacts: his 60-plus-year-old mother, who Loiza had never taught to text, but she’d figured it out anyway.

Mrs. Victor—Miss Vicky on the fortune-teller shingle that hung in the yard of the little Rosedale bungalow where Loiza lived with her—was a supportive mother. She knew how to compliment her son (she would find the Santa hat attractive but remind him red was not his lucky color), but her scary arthritic fingers rarely composed anything happy. Her texts tended to be more like commands from a demanding field general—imagine Patton with hemorrhoids flaring up.

While Grace ran a needle of red thread through the Santa suit and Jake hummed along with Andy Williams, Loiza read his mother’s missive. And sighed again.

“Be kind, Loiza,” Grace encouraged. “You only have one mother.”

Loiza dropped his forehead to the table, the pointy end of the Santa cap stretching toward Grace’s sewing kit.

Without removing the hat from Loiza’s head, Jake gently shook the pom-pom end and said, “Jingle, jingle, jingle,” which made Grace laugh and which Loiza would have found wonderfully out-of-character if not for what his mother wanted him to do.

Barry Smith was a 37-year-old elf. He wasn’t a real elf, he just dressed like one when the season—and crime—fit. He was actually 42. And his real name wasn’t Barry Smith, but it had been so long since he’d used his real name there were times he imagined he’d forgotten it. Just as well.

Barry’s elf suit was vibrant green and came with a pointed cap, which when he applied the realistic pointy tips to his ears, made him look absolutely comical and harmless—which was the point.

Barry, however, was neither comical nor harmless. Barry was particularly harmful. He may not have ever shot anyone, or stabbed them, bashed them over the head or poisoned them, but he had contributed to the early demise of many through the stress induced by his schemes and scams.

Some of his efforts were complex and leveraged the free-wheeling nature of cryptocurrency while others—such as his favorite holiday ritual of stealing gift cards—were more basic.

The crypto ploys—including what the media had coined “pig slaughtering”—were Barry’s most profitable ventures. Not that he invented them, but when there was a rip-off bandwagon, Barry could jump on as fast as the next guy. Pig slaughtering was actually a modernization of an ancient ruse—predating Charles Ponzi and his eponymous scheme—and possibly one of the first cons ever developed.

It worked thusly: find someone who was both gullible and had cash (their numbers were so surprisingly high Barry often marveled that anyone still had any money at all). Lure the mark into an investment (land development, oil wells) and provide a fast positive return on their money. The investment, like the profit, would be make-believe, so Barry had to make sure the mark was appropriately greedy and would come back for more. (Few disappointed in that regard, but if they did, Barry chalked up the loss and moved on.)

Once the mark’s appetite was whetted, Barry would come in for the kill, promising even bigger returns but the investment would also need to be larger. And so the soon-to-be-conned investor would hand over more money to Barry to add to the investing pool. Only, again, there was no pool. No investment. Just Barry’s pocket. At which point Barry would disappear with the money, change names, change cities, and start anew. It was a profitable living and Barry found the frequent change of locales refreshing.

But those deals were long games. They took time—lots and lots of time. And come Christmas, Barry just wanted some easy money. So he stole gift cards—not validated gift cards someone had bought, but the ones still on the grocery store racks, waiting to be purchased. The ones with printing on their logo-adorned sleeves advising the cards had no value until validated upon purchase.

The deal worked like this: Barry would steal handfuls (sometimes boxes full) of unvalidated gift cards. He’d take them home (currently a rented two-bedroom condo in a nice 15-floor building in Towson, half an hour north of Baltimore) where he lived across the hall from a guy from Yemen who was very successful in human trafficking (which Barry was not into, but everyone had to make a living).

Barry would give the stolen gift cards to that trafficking guy, who would take them to a small warehouse in one of those sections of Baltimore City realtors tried to pitch as “dynamic”, which was really camouflage for crime-ridden. The flat-roofed building, with bars over the smeary high windows and mysterious smoke coming out of a cinderblock chimney, was a place no one wondered enough about to look into what was going on inside, it being assumed the activity was very illegal and highly dangerous. Even Federal law enforcement with all its pay grades and perks didn’t make some enterprises worth investigating, because what good was that fat pension if you didn’t live long enough to collect it?

In that warehouse, small hands good at meticulous chores (and probably relieved not to be required to do far more sickening tasks) would set about surgically removing the gift cards from their cardboard holders, peeling off the security strip to uncover and note the validation code and/or pin, then replacing the original security strip with a new one (they were sold online), returning the gift card to its cardboard holder, then returning all the gift cards to Barry along with the corresponding validation codes.

Barry would then replace the gift cards on the store racks from where he’d stolen them. (The elf suit was often employed in both the theft and return of the gift cards, as Barry, in said elf suit, would provide cartoonish distraction while an accomplice slippery-fingered the gift cards either onto or off of the rack. It was also generally assumed that an elf—like a uniformed cable installer—could go anywhere without question, in season of course.)

Once Barry had the gift card validation codes, he’d enter them into an app he’d written, which would, multiple times every day, attempt to redeem those codes, in effect making the gift cards “go live”. Until a card Barry had stolen and returned to the racks was legitimately purchased, the redemption effort would fail. But eventually someone would buy the gift card, at which point Barry’s validation would go through and Barry would have a live gift card code he could add to an account at Amazon, Apple, or wherever (sometimes he sold the codes in bulk to cohorts in Asia who could spend that cash faster than a lightning strike).

The trick was that Barry needed to use those validated codes before they were redeemed by whoever purchased the card. Which was why he began the process in mid-November—the beginning of the busiest gift card buying season (more volume than Mother’s Day or graduation). Since most gift cards were bought to give as presents for Christmas or Hanukkah, they wouldn’t be redeemed for weeks after they were purchased.

For example, the timeline for the $200 gift card Barry used to buy a case of liquor for a Christmas Eve party in his building went like this: Barry stole the card (along with dozens more) on November 17th. On November 19th, he gave it to his Yemenis trafficking guy with the warehouse. On November 21st (a quick turnaround time, because those imprisoned little hands worked around the clock), Barry got the card back from the shady trafficking guy along with the validation code and pin number. On December 3rd, Barry returned the card to the end-cap display at a grocery store on York Rd. Every day after, Barry’s app tried to activate the card by entering the validation code and pin on the Visa website.

On December 10th, bingo: someone bought the gift card, and perhaps put it into an envelope with a Christmas card or stored it in a drawer, intending to use it as a stocking stuffer—whatever—most importantly, the buyer hadn’t used the card, which, by the time it ended up in the happy clutches of its intended recipient, would be worth zero, because Barry would have spent it. Which meant the gift receiver was going to be very disappointed. While the gift giver was going to be very embarrassed and probably confused at how the present for which they paid $200 was worthless. Barry didn’t know who the intended gift receiver or giver was and didn’t care.

Which was his mistake. Barry failed to anticipate that a gypsy fortune teller in Rosedale liked to give gift cards to the nice UPS man who always made sure the boxes of homemade prayer candles shipped to her from Romania were left inside the chain fence, on her side porch, under cover, out of the rain.

Loiza had been looking forward to Grace’s beef stew, which she served with homemade rosemary biscuits. Prison had not only been a circumstance that caused Grace to meet and fall in love with Jake but learn how to cook. Talk about silver linings.

Loiza could have stayed for dinner and undertaken his current task on his laptop, but Jake’s carriage house didn’t have the necessary bandwidth.

So Loiza was back home in the basement of his mother’s aluminum-sided bungalow, where the aroma wasn’t savory with stewing beef but witchy from candles burning upstairs, which his mother told her clients was the fragrance of frankincense, but Loiza associated with incinerating rubber and storm-soaked gardening mulch. It was an unpleasant sensory experience Loiza had endured since childhood, and when he used to complain it made him sick to his stomach his mother scolded him that he liked having the bills paid, didn’t he?

He once bought his mother a lavender candle from Bath and Body Works, but she ended up using it to try keeping squirrels out of the bird feeder (and when that failed, she went back to the pellet gun).

What his mother now wanted him to do—and “want” was the gentlest way to phrase her instructions—was find out how the gift card she gave the UPS man ended up with, as she said, “no money on it.”

Most people in Mrs. Victor’s position would go through the emotional stages of being victimized by gift card fraud: shock that such a thing could happen; more shock that such a thing could happen to them; embarrassment of having given a valueless gift; vulnerability to the possibility such a thing might happen again; paranoia that such a thing might have already happened and be lying in wait to be revealed; anger that someone had stolen from them; greater anger that companies who issued gift cards made it so easy for them to be stolen; even greater anger that companies who issued gift cards knew it was easy for gift cards to be stolen, kept selling them, and did little if anything to help victims recover their losses; and far greater anger that law enforcement was doing next to nothing about it, as if the fact no one had been shot in the commission of the crime was actually a relief; then, finally, depression would set in, because how had the world managed to become a place of such dreadful circumstances and why wasn’t life rosy and cheerful like on TikTok.

But Mrs. Victor’s emotional train ran on its own tracks. Which was why she told her son, “Whoever did this … you find them for me. Intelege-ma?” That last bit was Romanian—it meant, Understand? He’d heard that word a lot growing up. Heard it a lot now, too. Generally the words came with a finger pointed up at him.

Mrs. Victor may have been nearly two feet shorter than her six-foot-plus son, but her spirit was powerful and malevolent. And the dark evil that could turn her eyes into black holes…? That had sent hardened men three times her size running for the hills. Lots of bad people thought they’d seen the worst of the world, and maybe they had. But Mrs. Victor’s eyes could look like she was staring back from the tortured realms of eternity as if intent on dragging someone along with her.

Loiza knew that was all in his imagination … most of the time anyway. And he was a good son. He did what his mother asked.

It didn’t take long. Cybersecurity, being what is was—online degrees pitched from “schools” that advertised on late night TV?—the effective safety of the Internet was equivalent to legally-mandated shoulder harnesses and child car seats properly secured in the back seat offering protection against a head-on collision … with a runaway freight train … going downhill … loaded with explosives.

The validation code on the back of the gift card was all Loiza needed. He traced it to the store where his mother bought it. Discovered the date the nice UPS man tried to activate it was ten days after it had already been activated by someone else (likely either the thief or someone the thief had sold it to) and that those funds had been used to buy shoes on Amazon, order steamed crabs from a popular Timonium carry-out spot, and the balance had been applied toward a sizeable liquor purchase, as if someone was stocking up for a party.

Finding security footage of the actual transactions involving the the gift card proved the trickier part, as only the liquor store had a security system that worked. But, alas, maintained on a very unsecure (most were) cloud server, there, coming into the store to pick up the liquor purchased online with the stolen gift card, was a man in an elf suit, his holiday attire having provided for a very festive exchange of seasonal greetings.

Facial recognition—always improving—and access to motor vehicle records—always easy—provided Loiza with the elf’s name and address, and from there Loiza determined the man’s history, such as it was, including that his real name was not Barry and he lived across the hall from a very bad actor from Yemen who did very bad things to very many people, most of it taking place in a warehouse in a dynamic section of Baltimore City.

If law enforcement had the resources, or been told Intelege-ma by their mother, they could have discovered all of this. Although by the time they obtained the necessary warrants and cooperation from the various associated businesses and online providers, the pyramids would have crumbled to dust. Loiza was not hindered by such procedural complications.

After five hours in his mother’s basement, assisted by his bank of computers that drew more power than the rest of the house in a week, Loiza had what his mother wanted. At least he thought he did.

As Loiza informed his mother of the man’s name, gave her Barry’s background, the ins and outs of what had transpired with the gift card, the involvement of the man from Yemen, Mrs. Victor listened patiently, at one point even appreciatively patted his hand, then looked at him once he finished all he had to report, and after a moment—as Ella Fitzgerald sang White Christmas in the background and snow began to fall outside—told Loiza, Intelege-ma?

Which was why, on Christmas Eve, Jake was in Towson, dressed in the Santa suit Grace had altered to fit him.

There was still snow on the balcony railing of the third-floor condo in Barry’s building rented by a grad student named Corrine, who made a mean lasagna and was a furry. The first time Corrine and Barry had sex, she had him put on a teddy bear costume she kept in her closet. Barry had heard about sex like that, but didn’t think it was a real thing, then Corrine told him about furry fandom and the conventions she’d been to, but that he shouldn’t assume all furries liked to dress up for sex, some just did it for fun. Barry had made a comment about whatever floated someone’s boat.

Two weeks ago, when Corrine found out Barry had an elf costume, she got herself a fairy outfit, complete with magic wand, and they’ve been having regular costume-attired sex since.

Now, 3:35 in the afternoon on Christmas Eve, there was a tray of lasagna baking in the oven, Ray Charles sang about sleigh bells ringing, Corrine was half out of her fairy costume, and life for Barry was looking pretty damned sweet. Then his phone chimed with a text.

Then it chimed again. And again. And pretty soon it was one chime after another, which threatened to spoil the kinky mood. Barry was about to throw his phone against the wall when he saw the texts were from his banks—the banks in which he had accounts he paid taxes on and the banks no one was supposed to know about.

Every text alerted Barry to transfers of funds out of his accounts. Only Barry had not ordered any transfers, nor did he know anything about them other than, apparently, they were happening. His stomach twisted in knots because Barry realized: he was being robbed. It was nothing as visually melodramatic as masked bandits coming over the hill on horseback to hold-up the stagecoach, but robbery nonetheless. Only this was like being robbed by ghosts.

With no time to explain his hurried exit to Corrine, Barry, still in elf costume, raced out of the condo, bypassed the elevator for the stairs to save time, sprinted up a dozen flights to his condo, where, breathless and sweaty, heart-pounding with exertion and fear, he snapped open his laptop, and started doing all he could to slam the virtual doors on his accounts when the power went out.

Oh for the love of God, BGE, now! It was a little windy outside, and cold, but the snow from a few days ago had been plowed from the streets and sidewalks. Why was the power out? Barry took a deep breath and tried to recall a prayer about being granted the power to not get stressed about that which he could not control, or whatever that slogan had been when he did an unsuccessful court-ordered stint in AA years ago under one of his former aliases.

Okay—no electricity, he could deal. His laptop was fully charged. On battery power, he was bringing up his bank’s website when—no!—suddenly he was bringing up nothing because the building’s internet—included in his monthly HOA fee—went dark. So now Barry—instead of having Christmasy kinky sex with fairy Corrine or blocking Internet ghouls—was sprinting out of his condo.

He was still in his elf suit because there was no time to change. His nearest bank had a branch two blocks away and would only be open for another hour, and if he could get there in time, he might be able to salvage his ill-gotten net worth from completely disappearing into the world wide web.

As Barry ran down the hall, he was trailed by his Yemenis neighbor who had a panic bag slung over his shoulder. Even if the power was on, they’d be going down the stairs to save precious seconds.

Barry needed to get to his bank. His friend from Yemen needed to get out of the country, because he just learned that his warehouse was being raided by ICE, his well-bribed contact within said organization having been turned and was in custody, being transported to a place where Yemen would, one day, find him and have him killed.

The two men charged down the stairwell, which was dark, lit only by the glare of emergency lights on every other floor. As the soles of their shoes—Barry’s remained adorned with green felt—pounded the concrete steps, they passed a somewhat out-of-breath Santa Claus, laboriously making his way upward with a flower arrangement in his gloved hands—the tenth Santa that day to arrive with flowers, chocolates, bath salts, or, in one case, a willingness to sing Christmas carols while stripping for the bridge club that still had more spunk in them than might be guessed from the curvature of their spines.

Something about Santa triggered wariness in Barry—that instinct he had when something was amiss, or about to go wrong—and Barry was just about to turn around when the silently-fired bullet went through his head, splattering bone, blood, and brains, and the next few bullets finished the job, and the man from Yemen caught some collateral damage and tumbled to the landing between floors where he died with Barry on top of him. And the tinkle-tinkle sound was not icicles falling from the rooftops but spent shell casings rolling down the steps as Santa Claus, not so out of breath after all, tossed the bouquet on top of the miscreant duo and retreated down the stairs humming Andy Williams’ “It’s the Holiday Season.”

Christmas morning. Jake, in his Santa garb, and Grace, dressed as Mrs. Claus, were at the community center adjacent to central lock-up, giving out presents to kids who had a parent—in some cases two—in prison. Most of the kids hadn’t believed in Santa since they were three, but liked cool gifts and could, for a couple hours, manage to pretend their world wasn’t a hopeless glob of dog crap scraped off someone’s shoe. (If there was any doubt as to their inevitable plight, take a look at the city’s public school system, which was only slightly more functional—although smellier—than its sewer system.)

Today at least, a couple dozen kids would to get to play Bayonetta 3 on the Nintendo Switch many of them had just unwrapped—maybe even make it to chapter seven before someone swiped the gear out of their bedroom and sold it or used it to unwind after a tricky day on the corner hustling dime bags.

The way tech barons appraised geeky kids in garage start-ups as their future competition, Jake estimated some of these rascals would, in a few years’ time, be his competition and do hits for $75 he was currently getting paid ten grand for. But that was the nature of supply and demand, and consideration of quality workmanship only carried so much financial weight.

A few of the younger ones miraculously still had a sparkle of innocence in their eyes, but that candle was burning low, and unless some attention-starved celebrity or Instagram fun coach in need of mock-feel-good content swooped in and adopted them, misery was brightest star on their horizon.

The kids ended up with a lot more gifts this year than last, when Grace first helped out, because a surprise string of Christmas Eve donations had come in from anonymous donors, who Grace imagined was Loiza, because the money arrived from multiple online sources one right after the other. After buying lots of presents, there was even a nice hunk of money left over to help the legal arm of Parents Behind Bars finance the appeal of a woman who clearly had been framed and to the astonishment of all concerned—including the prosecutor and public defender—been convicted by a jury after the judge, who had he been half awake for the trial, should have thrown the whole thing out on the PD’s motion for acquittal at the end of the state’s case, and when that hadn’t happened, the flummoxed prosecutor had to rearrange his schedule because he’d assumed he’d have the rest of the day off and ended up having to explain to his ex-wife he was still in court and couldn’t pick up the kids for his bi-weekly visitation.

Meanwhile, in Rosedale, Mrs. Victor was preparing a turkey, stuffing, gravy, sauerkraut, green beans, and sweet potato casserole—which was nothing like the Christmas meals she’d had as a child in Romania—but the younger generation of her clan didn’t give a hoot about tradition and would be glued to their phones until Mrs. Victor gave them that scary look that would make the littlest ones cry. And then, for at least an hour, her little bungalow, usually inhabited only by Mrs. Victor and Loiza, would be free of Internet nonsense and instead be shoulder to shoulder with family, reunited from places up and down the east coast, returned to the city where their ancestors first settled and had been the A-rabs in the alley with the horse-drawn carts who sold fruits and vegetables, told fortunes, and ran games of chance at state fairs, among other things.

Loiza would come up from his screens in the basement, which by then would be scrubbed of the video he’d hacked from the security cameras of the warehouse where Barry the Elf’s now-deceased Yemenis neighbor had been keeping people in chains. Loiza had anonymously sent that video to ICE along with a note he was going to share it with the Washington Post in case law enforcement needed motivation to shut the place down.

Loiza would spend the rest of Christmas reconnecting with his many cousins, some of whom were married and had children, like Mrs. Victor hoped for Loiza one day. One day … but not too soon.

As Mrs. Victor basted her turkey, Jake and Grace, back in the city, left the community center in their Clausian outfits and were walking in the shadow of the razor-wire encircled building where Grace had been detained pending trial for killing her rotten-to-the-core husband what felt like a lifetime ago. She reached for Jake’s hand, which he held as they continued down the block.

“Nice children,” Grace commented of the kids they’d spent the morning with.

“Mm,” was the agreeable sound Jake made in reply—not exactly agreeing, but it was Christmas…

A few strides later, as she stepped over used drug needles, Grace returned to reality. She sighed, “The world is really awful, isn’t it?”

Jake squeezed her hand. “Not all of it.”

Although he’d become more of a talker over their months together, Jake still spent most of his time in silence, which made it so unusual for him to say something like that Grace felt as if his words were better than any Christmas gift she’d unwrap once they returned home. She leaned her head against his strong shoulder and warmly replied, “Merry Christmas to you, too.”

He kissed the top of her head. Back at his Cadillac, he opened the door for her.

Getting in the front seat, Grace said, “By the way, what was it Loiza’s mother got you for Christmas. I meant to ask earlier.”

“Gift card,” Jake replied.

Grace nodded. “Always a safe choice.”